Benjamin Fondane is a Scriptwriter Roumain born on 14 november 1898 at Iaşi (Roumanie)

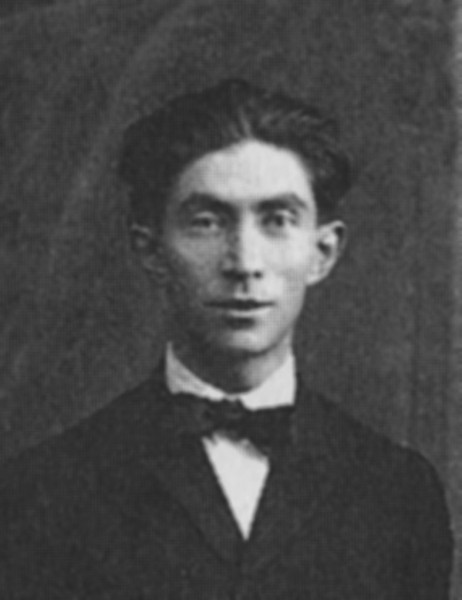

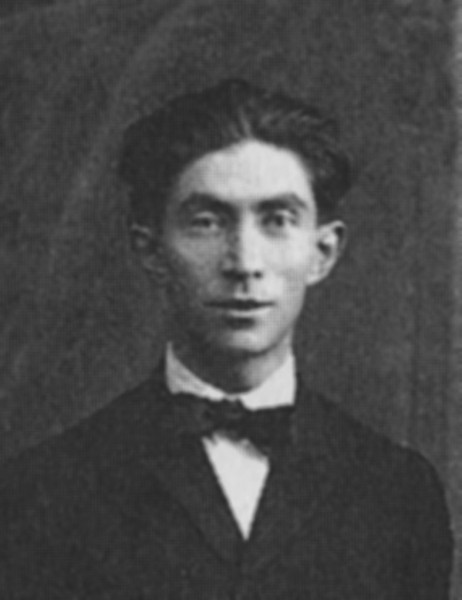

Benjamin Fondane ([bɛ̃ʒamɛ̃ fɔ̃dan]) or Benjamin Fundoianu ([benʒaˈmin fundoˈjanu]; born Benjamin Wechsler, Wexler or Vecsler, first name also Beniamin or Barbu, usually abridged to B.; November 14, 1898 – October 2, 1944) was a Romanian and French poet, critic and existentialist philosopher, also noted for his work in film and theater. Known from his Romanian youth as a Symbolist poet and columnist, he alternated Neoromantic and Expressionist themes with echoes from Tudor Arghezi, and dedicated several poetic cycles to the rural life of his native Moldavia. Fondane, who was of Jewish Romanian extraction and a nephew of Jewish intellectuals Elias and Moses Schwartzfeld, participated in both minority secular Jewish culture and mainstream Romanian culture. During and after World War I, he was active as a cultural critic, avant-garde promoter and, with his brother-in-law Armand Pascal, manager of the theatrical troupe Insula.

Fondane began a second career in 1923, when he moved to Paris. Affiliated with Surrealism, but strongly opposed to its communist leanings, he moved on to become a figure in Jewish existentialism and a leading disciple of Lev Shestov. His critique of political dogma, rejection of rationalism, expectation of historical catastrophe and belief in the soteriological force of literature were outlined in his celebrated essays on Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, as well as in his final works of poetry. His literary and philosophical activities helped him build close relationships with other intellectuals: Shestov, Emil Cioran, David Gascoyne, Jacques Maritain, Victoria Ocampo, Ilarie Voronca etc. In parallel, Fondane also had a career in cinema: a film critic and a screenwriter for Paramount Pictures, he later worked on Rapt with Dimitri Kirsanoff, and directed the since-lost film Tararira in Argentina.

A prisoner of war during the fall of France, Fondane was released and spent the occupation years in clandestinity. He was eventually captured and handed to Nazi German authorities, who deported him to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was sent to the gas chamber during the last wave of the Holocaust. His work was largely rediscovered later in the 20th century, when it became the subject of scholarly research and public curiosity in both France and Romania. In the latter country, this revival of interest also sparked a controversy over copyright issues.

Fondane was born in Iași, the cultural capital of Moldavia, on November 14, 1898, but, as he noted in a diary he kept at age 16, his birthday was officially recorded as November 15. Fondane was the only son of Isac Wechsler and his wife Adela (née Schwartzfeld), who also bore the sisters Lina (b. 1892) and Rodica (b. 1905), both of whom had careers in acting. Wechsler was a Jewish man from Hertza region, his ancestors having been born on the Fundoaia estate (which the poet later used as the basis for his signature). Adela was from an intellectual family, of noted influence within the urban Jewish community: her father, poet B. Schwartzfeld, was the owner of a book collection, while her uncles Elias and Moses both had careers in humanities. Adela herself was well acquainted with the intellectual elite of Iaşi, Jewish as well as ethnic Romanian, and kept recollections of her encounters with authors linked with the Junimea society. Through Moses Schwartzfeld, Fondane was also related with socialist journalist Avram Steuerman-Rodion, one of the literary men who nurtured the boy's interest in literature.

The young Benjamin was an avid reader, primarily interested in the Moldavian classics of Romanian literature (Ion Neculce, Miron Costin, Dosoftei, Ion Creangă), Romanian traditionalists or Neoromantics (Vasile Alecsandri, Ion Luca Caragiale, George Coșbuc, Mihai Eminescu) and French Symbolists. In 1909, after graduating from School No. 1 (an annex of the Trei Ierarhi Monastery), he was admitted into the Alexandru cel Bun secondary school, where he did not excel as a student. A restless youth (he recalled having had his first love affair at age 12, with a girl six years his senior), Fondane twice failed to get his remove before the age of 14.

Benjamin divided his time between the city and his father's native region. The latter's rural landscape impressed him greatly, and, enduring in his memory, became the setting in several of his poems. The adolescent Fondane took extended trips throughout northern Moldavia, making his debut in folkloristics by writing down samples of the narrative and poetic tradition in various Romanian-inhabited localities. Among his childhood friends was the future Yiddish-language writer B. Iosif, with whom he spent his time in Iaşi's Podul Vechi neighborhood. In this context, Fondane also met Yiddishist poet Jacob Gropper—an encounter which shaped Fondane's intellectual perspectives on Judaism and Jewish history. At the time, Fondane became known to his family and friends as Mieluşon (from miel, Romanian for "lamb", and probably in reference to his bushy hairdo), a name which he later used as a colloquial pseudonym.

Although Fondane later claimed to have started writing poetry at age eight, his earliest known contributions to the genre date from 1912, including both pieces of his own and translations from such authors as André Chénier, Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine and Henri de Régnier. The same year, some of these were published, under the pseudonym I. G. Ofir, in the local literary review Floare Albastră, whose owner, A. L. Zissu, was later a noted novelist and Zionist political figure. Later research proposed that these, like some other efforts of the 1910s, were collective poetry samples, resulting from a collaboration between Fondane and Gropper (the former was probably translating the latter's poetic motifs into Romanian). In 1913, Fondane also tried his hand at editing a student journal, signing his editorial with the pen name Van Doian, but only produced several handwritten copies of a single issue.

Debut years

Fondane's actual debut dates back to 1914, during the time when he became a student at the National High School Iaşi and formally affiliated with the provincial branch of the nation-wide Symbolist movement. That year, samples of lyric poetry were also published in the magazines Valuri and Revista Noastră (whose owner, poetess Constanţa Hodoş, even offered Fondane a job on the editorial board, probably unaware that she was corresponding with a high school student). Also in 1914, the Moldavian Symbolist venue Absolutio, edited by Isac Ludo, featured pieces he signed with the pen name I. Haşir. Among his National High School colleagues was Alexandru Al. Philippide, the future critic, who remained one of Fondane's best friends (and whose poetry Fondane proposed for publishing in Revista Noastră). Late in 1914, Fondane also began his short collaboration with the Iași Symbolist tribune Vieaţa Nouă. While several of his poems were published there, the review's founder Ovid Densusianu issued objections to their content, and, in their subsequent correspondence, each writer outlines his stylistic disagreements with the other.

During the first two years of World War I and Romania's neutrality, the young poet established new contacts within the literary environments of Iaşi and Bucharest. According to his brother-in-law and biographer Paul Daniel, "it is amazing how many pages of poetry, translations, prose, articles, chronicles have been written by Fundoianu in this interval." In 1915, four of his patriotic-themed poems were published on the front page of Dimineaţa daily, which campaigned for Romanian intervention against the Central Powers (they were the first of several contributions Fondane signed with the pen name Alex. Vilara, later

Al. Vilara). His parallel contribution to the Bârlad-based review Revista Critică (originally, Cronica Moldovei) was more strenuous: Fondane declared himself indignant that the editorial staff would not send him the galley proofs, and received instead an irritated reply from manager Al. Ştefănescu; he was eventually featured with poems in three separate issues of Revista Critică. At around that time, he also wrote a memoir of his childhood, Note dintr-un confesional ("Notes from a Confessional").

Around 1915, Fondane was discovered by the journalistic tandem of Tudor Arghezi and Gala Galaction, both of whom were also modernist authors, left-wing militants and Symbolist promoters. The pieces Fondane sent to Arghezi and Galaction's Cronica paper were received with enthusiasm, a reaction which surprised and impressed the young author. Although his poems went unpublished, his Iaşi-themed article A doua capitală ("The Second Capital"), signed Al. Vilara, was featured in an April 1916 issue. A follower of Arghezi, he was personally involved in raising awareness about Arghezi's unpublished verse, the Agate negre ("Black Diamonds") cycle.

Remaining close friends with Fondane, Galaction later made persistent efforts of introducing him to critic Garabet Ibrăileanu, with the purpose of having him published by the Poporanist Viața Românească review, but Ibrăileanu refused to recognize Fondane as an affiliate. Fondane had more success in contacting Flacăra review and its publisher Constantin Banu: on July 23, 1916, it hosted his sonnet Eglogă marină ("Marine Eglogue"). Between 1915 and 1923, Fondane also had a steady contribution to Romanian-language Jewish periodicals (Lumea Evree, Bar-Kochba, Hasmonaea, Hatikvah), where he published translations from international representatives of Yiddish literature (Hayim Nahman Bialik, Semyon Frug, Abraham Reisen etc.) under the signatures B. Wechsler, B. Fundoianu and F. Benjamin. Fondane also completed work on a translation of the Ahasverus drama, by the Jewish author Herman Heijermans.

His collaboration with the Bucharest-based Rampa (at the time a daily newspaper) also began in 1915, with his debut as theatrical chronicler, and later with his Carpathian-themed series in the travel writing genre, Pe drumuri de munte ("On Mountain Roads"). With almost one signed or unsigned piece per issue over the following years, Fondane was one of the more prolific contributors to that newspaper, and frequently made use of either pseudonyms (Diomed, Dio, Funfurpan, Const. Meletie) or initials (B. F., B. Fd., fd.). These included his January 1916 positive review of Plumb, the first major work by Romania's celebrated Symbolist poet, George Bacovia.

In besieged Moldavia and relocation to Bucharest

In 1917, after Romania joined the Entente side and was invaded by the Central Powers, Fondane was in Iaşi, where the Romanian authorities had retreated. It was in this context that he met and befriended the doyen of Romanian Symbolism, poet Ion Minulescu. Minulescu and his wife, author Claudia Millian, had left their home in occupied Bucharest, and, by spring 1917, hosted Fondane at their provisional domicile in Iaşi. Millian later recalled that her husband had been much impressed by the Moldavian teenager, describing him as "a rare bird" and "a poet of talent". The same year, at age 52, Isac Wechsler fell ill with typhus and died in Iaşi's Sfântul Spiridon Hospital, leaving his family without financial support.

At around that time, Fondane began work on the poetry cycle Priveliști ("Sights" or "Panoramas", finished in 1923). In 1918, he became one of the contributors to the magazine Chemarea, published in Iaşi by the leftist journalist N. D. Cocea, with help from Symbolist writer Ion Vinea. In the political climate marked by the Peace of Bucharest and Romania's remilitarization, Fondane used Cocea's publication to protest against the arrest of Arghezi, who had been accused of collaborationism with the Central Powers. In this context, Fondane spoke of Arghezi as being "Romania's greatest contemporary poet" (a verdict which was later to be approved of by mainstream critics). According to one account, Fondane also worked briefly as a fact checker for Arena, a periodical managed by Vinea and N. Porsenna. His time with Chemarea also resulted in the publication of his Biblical-themed short story Tăgăduinţa lui Petru ("Peter's Denial"). Issued by Chemarea's publishing house in 41 bibliophile copies (20 of which remained in Fondane's possession), it opened with the tract O lămurire despre simbolism ("An Explanation of Symbolism").

In 1919, upon the war's end, Benjamin Fondane settled in Bucharest, where he stayed until 1923. During this interval, he frequently changed domicile: after a stay at his sister Lina's home in Obor area, he moved on Lahovari Street (near Piața Romană), then in Moșilor area, before relocating to Văcărești (a majority Jewish residential area, where he lived in two successive locations), and ultimately to a house a short distance away from Foişorul de Foc. Between these changes of address, he established contacts with the Symbolist and avant-garde society of Bucharest: a personal friend of graphic artist Iosif Ross, he formed an informal avant-garde circle of his own, attended by writers F. Brunea-Fox, Ion Călugăru, Henri Gad, Sașa Pană, Claude Sernet-Cosma and Ilarie Voronca, as well as by artist-director Armand Pascal (who, in 1920, married Lina Fundoianu). Pană would later note his dominant status within the group, describing him as the "stooping green-eyed youth from Iași, the standard-bearer of the iconoclasts and rebels of the new generation".

The group was occasionally joined by other friends, among them Millian and painter Nicolae Tonitza. In addition, Fondane and Călugăru frequented the artistic and literary club established by the controversial Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești, a cultural promoter and political militant whose influence spread over several Symbolist milieus. In a 1922 piece for Rampa, he remembered Bogdan-Piteşti in ambivalent terms: "he could not stand moral elevation. [...] He was made of the greatest of joys, in the most purulent of bodies. How many generations of ancient boyars had come to pass, like unworthy dung, for this singular earth to be generated?"

Pressed on by his family and the prospects of financial security, Fondane contemplated becoming a lawyer. Having passed his baccalaureate examination in Bucharest, he was, according to his own account, a registered student at the University of Iași Law School, obtaining a graduation certificate but prevented from becoming a licentiate by the opposition of faculty member A. C. Cuza, the antisemitic political figure. According to a recollection of poet Adrian Maniu, Fondane again worked as a fact checker for some months after his arrival to the capital. His activity as a journalist also allowed him to interview Arnold Davidovich Margolin, statesman of the defunct Ukrainian People's Republic, with whom he discussed the fate of Ukrainian Jews before and after the Soviet Russian takeover.

Sburătorul, Contimporanul, Insula

Over the following years, he restarted his career in the press, contributing to various nationally circulated newspapers: Adevărul, Adevărul Literar şi Artistic, Cuvântul Liber, Mântuirea, etc. The main topics of his interest were literary reviews, essays reviewing the contribution of Romanian and French authors, various art chronicles, and opinion pieces on social or cultural issues. A special case was his collaboration with Mântuirea, a Zionist periodical founded by Zissu, where, between August and October 1919, he published his studies collection Iudaism şi elenism ("Judaism and Hellenism"). These pieces, alternating with similar articles by Galaction, showed how the young man's views in cultural anthropology had been shaped by his relationship with Gropper (with whom he nevertheless severed all contacts by 1920).

Fondane also renewed his collaboration with Rampa. He and another contributor to the magazine, journalist Tudor Teodorescu-Braniște, carried out a debate in the magazine's pages: Fondane's articles defended Romanian Symbolism against criticism from Teodorescu-Branişte, and offered glimpse into his personal interpretation of Symbolist attitudes. One piece he wrote in 1919, titled Noi, simboliștii ("Us Symbolists") stated his proud affiliation to the current (primarily defined by him as an artistic transposition of eternal idealism), and comprised the slogan: "We are too many not to be strong, and too few not to be intelligent." In May 1920, another of his Rampa contributions spoke out against Octavian Goga, Culture Minister of the Alexandru Averescu executive, who contemplated sacking George Bacovia from his office of clerk. The same year, Lumea Evree published his verse drama fragment Monologul lui Baltazar ("Belshazzar's Soliloquy").

Around the time of his relocation to Bucharest, Fondane first met the moderate modernist critic Eugen Lovinescu, and afterward became both an affiliate of Lovinescu's circle and a contributor to his literary review Sburătorul. Among his first contributions there was a retrospective coverage of the boxing match between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier, which comprised his reflections on the mythical power of sport and the clash of cultures. Although a Sburătorist, he was still in contact with Galaction and the left-wing circles. In June 1921, Galaction paid homage to "the daring Benjamin" in an article for Adevărul Literar şi Artistic, calling attention to Fondane's "overwhelming originality."

A year later, Fondane was employed by Vinea's new venue, the prestigious modernist venue Contimporanul. Having debuted in its first issue with a comment on Romanian translation projects (Ferestre spre Occident, "Windows on the Occident"), he was later assigned the theatrical column. Fondane's work was again featured in Flacăra magazine (at the time under Minulescu's direction): the poem Ce simplu ("How Simple") and the essay Istoria Ideii ("The History of the Idea") were both published there in 1922. The same year, with assistance from fellow novelist Felix Aderca, Fondane grouped his earlier essays on French literature as Imagini şi cărţi din Franţa ("Images and Books from France"), published by Editura Socec company. The book included what was probably the first Romanian study of Marcel Proust's contribution as a novelist. The author announced that he was planning a similar volume, grouping essays about Romanian writers, both modernists (Minulescu, Bacovia, Arghezi, Maniu, Galaction) and classics (Alexandru Odobescu, Ion Creangă, Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea, Anton Pann), but this work was not published in his lifetime.

Also in 1922, Fondane and Pascal set up the theatrical troupe Insula ("The Island"), which stated its commitment to avant-garde theater. Probably named after Minulescu's earlier Symbolist magazine, the group was likely a local replica of Jean Copeau's nonconformist productions in France. Hosted by the Maison d'Art galleries in Bucharest, the company was joined by, among others, actresses Lina Fundoianu-Pascal and Victoria Mierlescu, and director Sandu Eliad. Other participants were writers (Cocea, Pană, Zissu, Scarlat Callimachi, Mărgărita Miller Verghy, Ion Pillat) and theatrical people (George Ciprian, Marietta Sadova, Soare Z. Soare, Dida Solomon, Alice Sturdza, Ionel Ţăranu).

Although it stated its goal of revolutionizing the Romanian repertoire (a goal published as an art manifesto in Contimporanul), Insula produced mostly conventional Symbolist and Neoclassical plays: its inaugural shows included Legenda funigeilor ("Gossamer Legend") by Ștefan Octavian Iosif and Dimitrie Anghel, one of Lord Dunsany's Five Plays and (in Fondane's own translation) Molière's Le Médecin volant. Probably aiming to enrich this program with samples of Yiddish drama, Fondane began, but never finished, a translation of S. Ansky's The Dybbuk. The troupe ceased its activity in 1923, partly because of significant financial difficulties, and partly because of a rise in antisemitic activities, which put its Jewish performers at risk. For a while, Insula survived as a conference group, hosting modernist lectures on classical Romanian literature—with the participation of Symbolist and post-Symbolist authors such as Aderca, Arghezi, Millian, Pillat, Vinea, N. Davidescu, Perpessicius, and Fondane himself. He was at the time working on his own play, Filoctet ("Philoctetes", later finished as Philoctète).

Move to France

In 1923, Benjamin Fondane eventually left Romania for France, spurred on by the need to prove himself within a different cultural context. He was at the time interested in the success of Dada, an avant-garde movement launched abroad by the Romanian-born author Tristan Tzara, in collaboration with several others. Not dissuaded by the fact that his sister and brother-in-law (the Pascals) had returned impoverished from an extended stay in Paris, Fondane crossed Europe by train and partly by foot.

The writer (who adopted his Francized name shortly after leaving his native country) was eventually joined there by the Pascals. The three of them continued to lead a bohemian and at times precarious existence, discussed in Fondane's correspondence with Romanian novelist Liviu Rebreanu, and described by researcher Ana-Maria Tomescu as "humiliating poverty". The poet acquired some sources of income from his contacts in Romania: in exchange for his contribution to the circulation of Romanian literature in France, he received official funds from the Culture Ministry's directorate (at the time headed by Minulescu); in addition, he published unsigned articles in various newspapers, and even relied on handouts from Romanian actress Elvira Popescu (who visited his home, as did avant-garde painter M. H. Maxy). He also translated into French Zissu's novel Amintirile unui candelabru ("The Recollections of a Chandelier"). For a while, the poet also joined his colleague Ilarie Voronca on the legal department of L'Abeille insurance company.

After a period of renting furnished rooms, Fondane accepted an offer from Jean, brother of the deceased literary theorist Remy de Gourmont, and, employed as a librarian-concierge, moved into the Gourmonts' museum property on Rue des Saints-Pères, some distance away from to the celebrated literary café Les Deux Magots. In the six years before Pascal's 1929 death, Fondane left Gourmont's house and, with his sister and brother-in-law, moved into a succession of houses (on Rue Domat, Rue Jacob, Rue Monge), before settling into a historical building once inhabited by author Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (Rue Rollin, 6). Complaining about eye trouble and exhaustion, and several times threatened with insolvency, Fondane often left Paris for the resort of Arcachon.

Claudia Millian, who was also spending time in Paris, described Fondane's new focus on studying Christian theology and Catholic thought, from Hildebert to Gourmont's own Latin mystique (it was also at this stage that the Romanian writer acquired and sent home part of Gourmont's bibliophile collection). He coupled these activities with an interest in grouping together the cultural segments of the Romanian diaspora: around 1924, he and Millian were founding members of the Society of Romanian Writers in Paris, presided upon by the aristocrat Elena Văcărescu. Meanwhile, Fondane acquired a profile on the local literary scene, and, in his personal notes, claimed to have had his works praised by novelist André Gide and philosopher Jules de Gaultier. They both were his idols: Gide's work had shaped his own contribution in the prose poem genre, while Gaultier did the same for his philosophical outlook. The self-exiled debutant was nevertheless still viewing his career with despair, describing it as languishing, and noting that there was a chance of him failing to earn a solid literary reputation.

Surrealist episode

The mid-1920s brought Benjamin Fondane's affiliation with Surrealism, the post-Dada avant-garde current centered in Paris. Fondane also rallied with Belgian Surrealist composers E. L. T. Mesens and André Souris (with whom he signed a manifesto on modernist music), and supported Surrealist poet-director Antonin Artaud in his efforts to set up a theater named after Alfred Jarry (which was not, however, an all-Surrealist venue). In this context, he tried to persuade the French Surrealist group to tour his native country and establish contacts with local affiliates.

By 1926, Fondane grew disenchanted with the communist alignment proposed by the main Surrealist faction and its mentor, André Breton. Writing at the time, he commented that the ideological drive could prove fatal: "Perhaps never again will [a poet] recover that absolute freedom that he had in the bourgeois republic." A few years later, the Romanian writer expressed his support for the anti-Breton dissidents of Le Grand Jeu magazine, and was a witness at the 1930 riot which opposed the two factions. His anti-communist discourse was again aired in 1932: commenting on indictment of Surrealist poet Louis Aragon for communist texts (read by the authorities as instigation to murder), Fondane stated that he did believe Aragon's case was covered by the freedom of speech. His ideas also brought him into conflict with Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, who was moving away from an avant-garde background and into the realm of far right ideas. By the early 1930s, Fondane was in contact with the mainstream modernist Jacques Rivière and his Nouvelle Revue Française circle.

In 1928, his own collaboration with the Surrealists took shape as the book Trois scenarii: ciné-poèmes ("Three Scenarios: Cine-poems"), published by Documents internationaux de l'esprt nouveau collection, with artwork by American photographer Man Ray and Romanian painter Alexandru Brătăşanu (one of his other contacts in the French Surrealist photographers' group was Eli Lotar, the illegitimate son of Arghezi and nephew of Zissu). The "cine-poems" were intentionally conceived as unfilmable screenplays, in what was his personal statement about artistic compromise between experimental film and the emerging worldwide film industry. The book notably comprised his verdict about cinema being "the only art that was never classical."

Philosophical debut

With time, Fondane became a contributor to newspapers or literary journals in France, Belgium, and Switzerland: a regular presence in Cahiers du Sud of Carcassonne, he had his work featured in the Surrealist press (Discontinuité, Le Phare de Neuilly, Bifur), as well as in Le Courrier des Poètes, Le Journal des Poètes, Romain Rolland's Europe, Paul Valéry's Commerce etc. In addition, Fondane's research was hosted by specialized venues such as Revue Philosophique, Schweizer Annalen and Carlo Suarès' Cahiers de l'Étoile. After a long period of indecision, the Romanian poet became a dedicated follower of Lev Shestov, a Russian-born existentialist thinker whose ideas about the eternal opposition between faith and reason he expanded upon in later texts. According to intellectual historian Samuel Moyn, Fondane was, with Rachel Bespaloff, one of the "most significant and devoted of Shestov's followers". In 1929, as a frequenter of Shestov's circle, Fondane also met Argentinian female author Victoria Ocampo, who became his close friend (after 1931, he became a contributor to her modernist review, Sur). Fondane's essays were more frequently than before philosophical in nature: Europe published his tribute Shestov (January 1929) and his comments of Edmund Husserl's phenomenology, which included his own critique of rationalism (June 1930).

Invited (on Ocampo's initiative) by the Amigos del Arte society of Buenos Aires, Fondane left for Argentina and Uruguay in summer 1929. The object of his visit was promoting French cinema with a set of lectures in Buenos Aires, Montevideo and other cities (as he later stated in a Rampa interview with Sarina Cassvan-Pas, he introduced South Americans to the work of Germaine Dulac, Luis Buñuel and Henri Gad). In this context, Fondane met essayist Eduardo Mallea, who invited him to contribute in La Nación's literary supplement. His other activities there included conferencing on Shestov at the University of Buenos Aires and publishing articles on several subjects (from Shestov's philosophy to the poems of Tzara), but the fees received in return were, in his own account, too small to cover the cost of decent living.

In October 1929, Fondane was back in Paris, where he focused on translating and popularizing some of Romanian literature's milestone texts, from Mihai Eminescu's Sărmanul Dionis to the poetry of Ion Barbu, Minulescu, Arghezi and Bacovia. In the same context, the expatriate writer helped introduce Romanians to some of the new European tendencies, becoming, in the words of literary historian Paul Cernat, "the first important promoter of French Surrealism in Romanian culture."

Integral and unu

In the mid-1920s, Fondane and painter János Mattis-Teutsch joined the external editorial board of Integral magazine, an avant-garde tribune published in Bucharest by Ion Călugăru, F. Brunea-Fox and Voronca. He was assigned a permanent column, known as Fenêtres sur l'Europe/Ferestre spre Europa (French and Romanian for "Windows on Europe"). With Barbu Florian, Fondane became a leading film reviewer for the magazine, pursuing his agenda in favor of non-commercial and "pure" films (such as René Clair's Entr'acte), and praising Charlie Chaplin for his lyricism, but later making some concessions to talkies and the regular Hollywood films. Exploring what he defined as "the great ballet of contemporary French poetry", Fondane also published individual notes on writers Aragon, Jean Cocteau, Joseph Delteil, Paul Éluard and Pierre Reverdy. In 1927, Integral also hosted one of Fondane's replies to the communist Surrealists in France, as Le surréalisme et la révolution ("Surrealism and Revolution").

He also came into contact with unu, the Surrealist venue of Bucharest, which was edited by several of his avant-garde friends at home. His contributions there included a text on Tzara's post-Dada works, which he analyzed as Valéry-like "pure poetry". In December 1928, unu published some of Fondane's messages home, as Scrisori pierdute ("Lost Letters"). Between 1931 and 1934, Fondane was in regular correspondence with the unu writers, in particular Stephan Roll, F. Brunea-Fox and Saşa Pană, being informed about their conflict with Voronca (attacked as a betrayer of the avant-garde) and witnessing from afar the eventual implosion of Romanian Surrealism on the model of French groups. In such dialogues, Roll complains about right-wing political censorship in Romania, and speaks in some detail about his own conversion to Marxism.

With Fondane's approval and Minulescu's assistance, Privelişti also saw print in Romania during 1930. Published by Editura Cultura Naţională, it sparked significant controversy with its nonconformist style, but also made the author the target of critics' interest. As a consequence, Fondane was also sending material to Isac Ludo's Adam review, most of it notes (some hostile) clarifying ambiguous biographical detail discussed in Aderca's chronicle to Privelişti. His profile within the local avant-garde was also acknowledged in Italy and Germany: the Milanese magazine Fiera Letteraria commented on his poetry, reprinting fragments originally featured in Integral; in its issue of August–September 1930, the Expressionist tribune Der Sturm published samples of his works, alongside those of nine other Romanian modernists, translated by Leopold Kosch.

As Paul Daniel notes, the polemics surrounding Privelişti only lasted for a year, and Fondane was largely forgotten by the Romanian public after this moment. However, the discovery of Fondane's avant-garde stance by traditionalist circles took the form of bemusement or indignation, which lasted into the next decades. The conservative critic Const. I. Emilian, whose 1931 study discussed modernism as a psychiatric condition, mentioned Fondane as one of the leading "extremists", and deplored his abandonment of traditionalist subjects. Some nine years later, the antisemitic far right newspaper Sfarmă-Piatră, through the voice of Ovidiu Papadima, accused Fondane and "the Jews" of having purposefully maintained "the illusion of a literary movement" under Lovinescu's leadership. Nevertheless, before that date, Lovinescu himself had come to criticize his former pupil (a disagreement which echoed his larger conflict with the unu group). Also in the 1930s, Fondane's work received coverage in the articles of two other maverick modernists: Perpessicius, who viewed it with noted sympathy, and Lucian Boz, who found his new poems touched by "prolixity".

Rimbaud le voyou, Ulysse and intellectual prominence

Back in France, where he had become Shestov's assistant, Fondane was beginning work on other books: the essay on 19th-century poet Arthur Rimbaud—Rimbaud le voyou ("Rimbaud the Hoodlum")—and, despite an earlier pledge not to return to poetry, a new series of poems. His eponymously titled study-portrait of German philosopher Martin Heidegger was published by Cahiers du Sud in 1932. Despite his earlier rejection of commercial films, Fondane eventually became an employee of Paramount Pictures, probably spurred on by his need to finance a personal project (reputedly, he was accepted there with a second application, his first one having been rejected in 1929). He worked first as an assistant director, before turning to screenwriting. Preserving his interest in Romanian developments, he visited the Paris set of Televiziune, a Romanian cinema production for which he shared directorial credits. His growing interest in Voronca's own poetry led him to review it for Tudor Arghezi's Bucharest periodical, Bilete de Papagal, where he stated: "Mr. Ilarie Voronca is at the top of his form. I'm gladly placing my stakes on him."

In 1931, the poet married Geneviève Tissier, a trained jurist and lapsed Catholic. Their home on Rue Rollin subsequently became a venue for literary sessions, mostly grouping the Cahiers du Sud contributors. The aspiring author Paul Daniel, who became Rodica Wechsler's husband in 1935, attended such meetings with his wife, and recalls having met Gaultier, filmmaker Dimitri Kirsanoff, music critic Boris de Schlözer, poets Yanette Delétang-Tardif and Thérèse Aubray, as well as Shestov's daughter Natalie Baranoff. Fondane also enjoyed a warm friendship with Constantin Brâncuși, the Romanian-born modern sculptor, visiting Brâncuși's workshop on an almost daily basis and writing about his work in Cahiers de l'Étoile. He witnessed first-hand and described Brâncuși's primitivist techniques, likening his work to that of a "savage man".

Rimbaud le voyou was eventually published by Denoël & Steele company in 1933, the same year when Fondane published his poetry volume Ulysse ("Ulysses") with Les Cahiers du Journal des Poètes. The Rimbaud study, partly written as a reply to Roland de Renéville's monograph Rimbaud le Voyant ("Rimbaud the Seer"), consolidated Fondane's international reputation as a critic and literary historian. In the months after its publication, the book earned much praise from scholars and writers—from Joë Bousquet, Jean Cocteau, Benedetto Croce and Louis-Ferdinand Céline, to Jean Cassou, Guillermo de Torre and Miguel de Unamuno. It also found admirers in the English poet David Gascoyne, who was afterward in correspondence with Fondane, and the American novelist Henry Miller. Ulysse itself illustrated Fondane's interest in scholarly issues: he sent one autographed copy to Raïssa Maritain, wife of Jacques Maritain (both of whom were Catholic thinkers). Shortly after this period, the author was surprised to read Voronca's own French-language volume Ulysse dans la cité ("Ulysses in the City"): although puzzled by the similarity of titles with his own collection, he described Voronca as a "great poet." Also then, in Romania, B. Iosif completed the Yiddish translation of Fondane's Psalmul leprosului ("The Leper's Psalm"). The text, left in his care by Fondane before his 1923 departure, was first published in Di Woch, a periodical set up in Romania by poet Yankev Shternberg (October 31, 1934).

Anti-fascist causes and filming of Rapt

The 1933 establishment of a Nazi regime in Germany brought Fondane into the camp of anti-fascism. In December 1934, his Apelul studenţimii ("The Call of Students") was circulated among the Romanian diaspora, and featured passionate calls for awareness: "Tomorrow, in concentration camps, it will be to late". The following year, he outlined his critique of all kinds of totalitarianism, L'Écrivain devant la révolution ("The Writer Facing the Revolution"), supposed to be delivered in front of the Paris-held International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture (organized by left-wing and communist intellectuals with support from the Soviet Union). According to historian Martin Stanton, Fondane's activity in film, like Jean-Paul Sartre's parallel beginnings as a novelist, was itself a political statement in support of the Popular Front: "[they were] hoping to introduce critical dimensions in the fields they felt the fascists had colonized." Fondane nevertheless ridiculed the communist version of pacifism as a "parade of big words", noting that it opposed mere slogans to concrete German re-armament. Writing for the film magazine Les Cahiers Jaunes in 1933, he expressed the ambition of creating "an absurd film about something absurd, to satisfy [one's] absurd taste for freedom".

Fondane left the Paramount studios the same year, disappointed with company policies and without having had any screen credit of his own (although, he claimed, there were over 100 Paramount scripts to which he had unsigned contributions). During 1935, he and Kirsanoff were in Switzerland, for the filming of Rapt, with a screenplay by Fondane (adapted from Charles Ferdinand Ramuz's La séparation des races novel). The result was a highly poetic production, and, despite Fondane's still passionate defense of silent film, the first talkie in Kirsanoff's career. The poet was enthusiastic about this collaboration, claiming that it had enjoyed a good reception from Spain to Canada, standing as a manifesto against the success of more "chatty" sound films. In particular, French critics and journalists hailed Rapt as a necessary break with the comédie en vaudeville tradition. In the end, however, the independent product could not compete with the Hollywood industry, which was at the time monopolizing the French market. In parallel with these events, Fondane followed Shestov's personal guidance and, by means of Cahiers du Sud, attacked philosopher Jean Wahl's secular reinterpretation of Søren Kierkegaard's Christian existentialism.

From Tararira to World War II

Despite selling many copies of his books and having Rapt played at the Panthéon Cinema, Benjamin Fondane was still facing major financial difficulties, accepting a 1936 offer to write and assist in the making of Tararira, an avant-garde musical product of the Argentine film industry. This was his second option: initially, he contemplated filming a version of Ricardo Güiraldes' Don Segundo Sombra, but met opposition from Güiraldes' widow. While en route to Argentina, he became friends with Georgette Gaucher, a Breton woman, with whom he was in correspondence for the rest of his life.

Under contract with the Falma-film company, Fondane was received with honors by the Romanian Argentine community, and, with the unusual cut of his preferred suit, is said to have even become a trendsetter in local fashion. For Ocampo and the Sur staff, literary historian Rosalie Sitman notes, his visit also meant an occasion to defy the xenophobic and antisemitic agenda of Argentine nationalist circles. Centered on the tango, Fondane's film enlisted contributions from some leading figures in several national film and music industries, having Miguel Machinandiarena as producer and John Alton as editor; in starred, among others, Orestes Caviglia, Miguel Gómez Bao and Iris Marga. The manner in which Tararira approached its subject scandalized the Argentine public, and it was eventually rejected by its distributors (no copies survive, but writer Gloria Alcorta, who was present at a private screening, rated it a "masterpiece"). Fondane, who had earlier complained about the actors' resistance to his ideas, left Argentina before the film was actually finished. It was on his return trip that he met Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, with whom he and Geneviève became good friends.

With the money received in Buenos Aires, the writer contemplated returning on a visit to Romania, but he abandoned all such projects later in 1936, instead making his way to France. He followed up on his publishing activity in 1937, when his selected poems, Titanic, saw print. Encouraged by the reception given to Rimbaud le voyou, he published two more essays with Denoël & Steele: La Conscience malheureuse ("The Unhappy Consciousness", 1937) and Faux traité d'esthétique ("False Treatise of Aesthetics", 1938). In 1938, he was working on a collected edition of his Ferestre spre Europa, supposed to be published in Bucharest but never actually seeing print. At around that date, Fondane was also a presenter for the Romanian edition of 20th Century Fox's international newsreel, Movietone News.

In 1939, Fondane was naturalized French. This followed an independent initiative of the Société des écrivains français professional association, in recognition for his contribution to French letters. Cahiers du Sud collected the required 3,000 francs fee through a public subscription, enlisting particularly large contributions from music producer Renaud de Jouvenel (brother of Bertrand de Jouvenel) and philosopher-ethnologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl. Only months after this event, with the outbreak of World War II, Fondane was drafted into the French Army. During most of the "Phoney War" interval, considered too old for active service, he was in the military reserve force, but in February 1940 was called under arms with the 216 Artillery Regiment. According to Lina, "he left [home] with unimaginable courage and faith." Stationed at the Sainte Assise Castle in Seine-Port, he edited and stenciled a humorous gazette, L'Écho de la I C-ie ("The 1st Company Echo"), where he also published his last-ever work of poetry, Le poète en patrouille ("The Poet on Patrolling Duty").

First captivity and clandestine existence

Fondane was captured by the Germans in June 1940 (shortly before the fall of France), and was taken into a German camp as a prisoner of war. He managed to escape captivity, but was recaptured in short time. After falling ill with appendicitis, he was transported back to Paris, kept in custody at the Val-de-Grâce, and operated on. Fondane was eventually released, the German occupiers having decided that he was no longer fit for soldierly duty.

He was working on two poetry series, Super Flumina Babylonis (a reference to Psalm 137) and L'Exode ("The Exodus"), as well as on his last essay, focusing on 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire, and titled Baudelaire et l'expérience du gouffre ("Baudelaire and the Experience of the Abyss"). In addition to these, his other French texts, incomplete or unpublished by 1944, include: the poetic drama pieces Philoctète, Les Puits de Maule ("Maule's Well", an adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables) and Le Féstin de Balthazar ("Belshazzar's Feast"); a study about the life and work of Romanian-born philosopher Stéphane Lupasco; and the selection from his interviews with Shestov, Sur les rives de l'Illisus ("On the Banks of the Illisus"). His very last text is believed to be a philosophical essay, Le Lundi existentiel ("The Existential Monday"), on which Fondane was working in 1944. Little is known about Provèrbes ("Proverbs"), which, he announced in 1933, was supposed to be an independent collection of poems.

According to various accounts, Fondane made a point of not leaving Paris, despite the growing restrictions and violence. However, others note that, as a precaution against the antisemitic measures in the occupied north, he eventually made his way into the more permissive zone libre, and only made returns to Paris in order to collect his books. Throughout this interval, the poet refused to wear the yellow badge (mandatory for Jews), and, living in permanent risk, isolated himself from his wife, adopting an even more precarious lifestyle. He was still in contact with writers of various ethnic backgrounds, and active on the clandestine literary scene. In this context, Fondane stated his intellectual affiliation to the French Resistance: his former Surrealist colleague Paul Éluard published several of his poems in the pro-communist Europe, under the name of Isaac Laquedem (a nod to the Wandering Jew myth). Such pieces were later included, but left unsigned, in the anthology L'Honneur des poètes ("The Honor of Poets"), published by the Resistance activists as an anti-Nazi manifesto. Fondane also preserved his column in Cahiers du Sud for as long as it was possible, and had his contributions published in several other clandestine journals.

After 1941, Fondane became friends with another Romanian existentialist in France, the younger Emil Cioran. Their closeness signaled an important stage in the latter's career: Cioran was slowly moving away from his fascist sympathies and his antisemitic stance, and, although still connected to the revolutionary fascist Iron Guard, had reintroduced cosmopolitanism to his own critique of Romanian society. In 1943, transcending ideological boundaries, Fondane also had dinner with Mircea Eliade, the Romanian novelist and philosopher, who, like their common friend Cioran, had an ambiguous connection with the far right. In 1942, his own Romanian citizenship rights, granted by the Jewish emancipation of the early 1920s, were lost with the antisemitic legislation adopted by the Ion Antonescu regime, which also officially banned his entire work as "Jewish". At around that time, his old friends outside France made unsuccessful efforts to obtain him a safe conduct to neutral countries. Such initiatives were notably taken by Jacques Maritain from his new home in the United States and by Victoria Ocampo in Argentina.

Arrest, deportation and death

He was eventually arrested by collaborationist forces in spring 1944, after unknown civilians reported his Jewish origin. Held in custody by the Gestapo, he was assigned to the local network of Holocaust perpetrators: after internment in the Drancy transit camp, he was sent on one of the transports to the extermination camps in occupied Poland, reaching Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the meantime, his family and friends remained largely unaware of his fate. After news of his arrest, several of his friends reportedly intervened to save him, including Cioran, Lupasco and writer Jean Paulhan. According to some accounts, such efforts may have also involved another one of Cioran's friends, essayist Eugène Ionesco (later known for his work in drama).

Accounts differ on what happened to his sister Lina. Paul Daniel believes that she decided to go looking for her brother, also went missing, and, in all probability, became a victim of another deportation. Other sources state that she was arrested at around the same time as, or even together with, her brother, and that they were both on the same transport to Auschwitz. According to other accounts, Fondane was in custody while his sister was not, and sent her a final letter from Drancy; Fondane, who had theoretical legal grounds for being spared deportation (a Christian wife), aware that Lina could not invoke them, sacrificed himself to be by her side. While in Drancy, he sent another letter, addressed to Geneviève, in which he asked for all his French poetry to be published in the future as Le Mal des fantômes ("The Ache of Phantoms"), and optimistically called himself "the traveler who isn't done traveling".

While Lina is believed to have been marked for death upon arrival (and immediately after sent to the gas chamber), her brother survived the camp conditions for a few more months. He befriended two Jewish doctors, Moscovici and Klein, with whom he spent his free moments engaged in passionate discussions about philosophy and literature. As was later attested by a survivor of the camp, the poet himself was among the 700 inmates selected for extermination on October 2, 1944, when the Birkenau subsection outside Brzezinka was being evicted by SS guards. He was aware of impending death, and reportedly saw it as ironic that it came so near to an expected Allied victory. After a short interval in Block 10, where he is said to have awaited his death with dignity and courage, he was driven to the gas chamber and murdered. His body was cremated, along with those of the other victims.

Source : Wikidata

Benjamin Fondane

Nationality Roumanie

Birth 14 november 1898 at Iaşi (Roumanie)

Death 2 october 1944 (at 45 years) at Auschwitz concentration camp (Pologne)

Birth 14 november 1898 at Iaşi (Roumanie)

Death 2 october 1944 (at 45 years) at Auschwitz concentration camp (Pologne)

Fondane began a second career in 1923, when he moved to Paris. Affiliated with Surrealism, but strongly opposed to its communist leanings, he moved on to become a figure in Jewish existentialism and a leading disciple of Lev Shestov. His critique of political dogma, rejection of rationalism, expectation of historical catastrophe and belief in the soteriological force of literature were outlined in his celebrated essays on Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, as well as in his final works of poetry. His literary and philosophical activities helped him build close relationships with other intellectuals: Shestov, Emil Cioran, David Gascoyne, Jacques Maritain, Victoria Ocampo, Ilarie Voronca etc. In parallel, Fondane also had a career in cinema: a film critic and a screenwriter for Paramount Pictures, he later worked on Rapt with Dimitri Kirsanoff, and directed the since-lost film Tararira in Argentina.

A prisoner of war during the fall of France, Fondane was released and spent the occupation years in clandestinity. He was eventually captured and handed to Nazi German authorities, who deported him to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was sent to the gas chamber during the last wave of the Holocaust. His work was largely rediscovered later in the 20th century, when it became the subject of scholarly research and public curiosity in both France and Romania. In the latter country, this revival of interest also sparked a controversy over copyright issues.

Biography

Early lifeFondane was born in Iași, the cultural capital of Moldavia, on November 14, 1898, but, as he noted in a diary he kept at age 16, his birthday was officially recorded as November 15. Fondane was the only son of Isac Wechsler and his wife Adela (née Schwartzfeld), who also bore the sisters Lina (b. 1892) and Rodica (b. 1905), both of whom had careers in acting. Wechsler was a Jewish man from Hertza region, his ancestors having been born on the Fundoaia estate (which the poet later used as the basis for his signature). Adela was from an intellectual family, of noted influence within the urban Jewish community: her father, poet B. Schwartzfeld, was the owner of a book collection, while her uncles Elias and Moses both had careers in humanities. Adela herself was well acquainted with the intellectual elite of Iaşi, Jewish as well as ethnic Romanian, and kept recollections of her encounters with authors linked with the Junimea society. Through Moses Schwartzfeld, Fondane was also related with socialist journalist Avram Steuerman-Rodion, one of the literary men who nurtured the boy's interest in literature.

The young Benjamin was an avid reader, primarily interested in the Moldavian classics of Romanian literature (Ion Neculce, Miron Costin, Dosoftei, Ion Creangă), Romanian traditionalists or Neoromantics (Vasile Alecsandri, Ion Luca Caragiale, George Coșbuc, Mihai Eminescu) and French Symbolists. In 1909, after graduating from School No. 1 (an annex of the Trei Ierarhi Monastery), he was admitted into the Alexandru cel Bun secondary school, where he did not excel as a student. A restless youth (he recalled having had his first love affair at age 12, with a girl six years his senior), Fondane twice failed to get his remove before the age of 14.

Benjamin divided his time between the city and his father's native region. The latter's rural landscape impressed him greatly, and, enduring in his memory, became the setting in several of his poems. The adolescent Fondane took extended trips throughout northern Moldavia, making his debut in folkloristics by writing down samples of the narrative and poetic tradition in various Romanian-inhabited localities. Among his childhood friends was the future Yiddish-language writer B. Iosif, with whom he spent his time in Iaşi's Podul Vechi neighborhood. In this context, Fondane also met Yiddishist poet Jacob Gropper—an encounter which shaped Fondane's intellectual perspectives on Judaism and Jewish history. At the time, Fondane became known to his family and friends as Mieluşon (from miel, Romanian for "lamb", and probably in reference to his bushy hairdo), a name which he later used as a colloquial pseudonym.

Although Fondane later claimed to have started writing poetry at age eight, his earliest known contributions to the genre date from 1912, including both pieces of his own and translations from such authors as André Chénier, Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine and Henri de Régnier. The same year, some of these were published, under the pseudonym I. G. Ofir, in the local literary review Floare Albastră, whose owner, A. L. Zissu, was later a noted novelist and Zionist political figure. Later research proposed that these, like some other efforts of the 1910s, were collective poetry samples, resulting from a collaboration between Fondane and Gropper (the former was probably translating the latter's poetic motifs into Romanian). In 1913, Fondane also tried his hand at editing a student journal, signing his editorial with the pen name Van Doian, but only produced several handwritten copies of a single issue.

Debut years

Fondane's actual debut dates back to 1914, during the time when he became a student at the National High School Iaşi and formally affiliated with the provincial branch of the nation-wide Symbolist movement. That year, samples of lyric poetry were also published in the magazines Valuri and Revista Noastră (whose owner, poetess Constanţa Hodoş, even offered Fondane a job on the editorial board, probably unaware that she was corresponding with a high school student). Also in 1914, the Moldavian Symbolist venue Absolutio, edited by Isac Ludo, featured pieces he signed with the pen name I. Haşir. Among his National High School colleagues was Alexandru Al. Philippide, the future critic, who remained one of Fondane's best friends (and whose poetry Fondane proposed for publishing in Revista Noastră). Late in 1914, Fondane also began his short collaboration with the Iași Symbolist tribune Vieaţa Nouă. While several of his poems were published there, the review's founder Ovid Densusianu issued objections to their content, and, in their subsequent correspondence, each writer outlines his stylistic disagreements with the other.

During the first two years of World War I and Romania's neutrality, the young poet established new contacts within the literary environments of Iaşi and Bucharest. According to his brother-in-law and biographer Paul Daniel, "it is amazing how many pages of poetry, translations, prose, articles, chronicles have been written by Fundoianu in this interval." In 1915, four of his patriotic-themed poems were published on the front page of Dimineaţa daily, which campaigned for Romanian intervention against the Central Powers (they were the first of several contributions Fondane signed with the pen name Alex. Vilara, later

Al. Vilara). His parallel contribution to the Bârlad-based review Revista Critică (originally, Cronica Moldovei) was more strenuous: Fondane declared himself indignant that the editorial staff would not send him the galley proofs, and received instead an irritated reply from manager Al. Ştefănescu; he was eventually featured with poems in three separate issues of Revista Critică. At around that time, he also wrote a memoir of his childhood, Note dintr-un confesional ("Notes from a Confessional").

Around 1915, Fondane was discovered by the journalistic tandem of Tudor Arghezi and Gala Galaction, both of whom were also modernist authors, left-wing militants and Symbolist promoters. The pieces Fondane sent to Arghezi and Galaction's Cronica paper were received with enthusiasm, a reaction which surprised and impressed the young author. Although his poems went unpublished, his Iaşi-themed article A doua capitală ("The Second Capital"), signed Al. Vilara, was featured in an April 1916 issue. A follower of Arghezi, he was personally involved in raising awareness about Arghezi's unpublished verse, the Agate negre ("Black Diamonds") cycle.

Remaining close friends with Fondane, Galaction later made persistent efforts of introducing him to critic Garabet Ibrăileanu, with the purpose of having him published by the Poporanist Viața Românească review, but Ibrăileanu refused to recognize Fondane as an affiliate. Fondane had more success in contacting Flacăra review and its publisher Constantin Banu: on July 23, 1916, it hosted his sonnet Eglogă marină ("Marine Eglogue"). Between 1915 and 1923, Fondane also had a steady contribution to Romanian-language Jewish periodicals (Lumea Evree, Bar-Kochba, Hasmonaea, Hatikvah), where he published translations from international representatives of Yiddish literature (Hayim Nahman Bialik, Semyon Frug, Abraham Reisen etc.) under the signatures B. Wechsler, B. Fundoianu and F. Benjamin. Fondane also completed work on a translation of the Ahasverus drama, by the Jewish author Herman Heijermans.

His collaboration with the Bucharest-based Rampa (at the time a daily newspaper) also began in 1915, with his debut as theatrical chronicler, and later with his Carpathian-themed series in the travel writing genre, Pe drumuri de munte ("On Mountain Roads"). With almost one signed or unsigned piece per issue over the following years, Fondane was one of the more prolific contributors to that newspaper, and frequently made use of either pseudonyms (Diomed, Dio, Funfurpan, Const. Meletie) or initials (B. F., B. Fd., fd.). These included his January 1916 positive review of Plumb, the first major work by Romania's celebrated Symbolist poet, George Bacovia.

In besieged Moldavia and relocation to Bucharest

In 1917, after Romania joined the Entente side and was invaded by the Central Powers, Fondane was in Iaşi, where the Romanian authorities had retreated. It was in this context that he met and befriended the doyen of Romanian Symbolism, poet Ion Minulescu. Minulescu and his wife, author Claudia Millian, had left their home in occupied Bucharest, and, by spring 1917, hosted Fondane at their provisional domicile in Iaşi. Millian later recalled that her husband had been much impressed by the Moldavian teenager, describing him as "a rare bird" and "a poet of talent". The same year, at age 52, Isac Wechsler fell ill with typhus and died in Iaşi's Sfântul Spiridon Hospital, leaving his family without financial support.

At around that time, Fondane began work on the poetry cycle Priveliști ("Sights" or "Panoramas", finished in 1923). In 1918, he became one of the contributors to the magazine Chemarea, published in Iaşi by the leftist journalist N. D. Cocea, with help from Symbolist writer Ion Vinea. In the political climate marked by the Peace of Bucharest and Romania's remilitarization, Fondane used Cocea's publication to protest against the arrest of Arghezi, who had been accused of collaborationism with the Central Powers. In this context, Fondane spoke of Arghezi as being "Romania's greatest contemporary poet" (a verdict which was later to be approved of by mainstream critics). According to one account, Fondane also worked briefly as a fact checker for Arena, a periodical managed by Vinea and N. Porsenna. His time with Chemarea also resulted in the publication of his Biblical-themed short story Tăgăduinţa lui Petru ("Peter's Denial"). Issued by Chemarea's publishing house in 41 bibliophile copies (20 of which remained in Fondane's possession), it opened with the tract O lămurire despre simbolism ("An Explanation of Symbolism").

In 1919, upon the war's end, Benjamin Fondane settled in Bucharest, where he stayed until 1923. During this interval, he frequently changed domicile: after a stay at his sister Lina's home in Obor area, he moved on Lahovari Street (near Piața Romană), then in Moșilor area, before relocating to Văcărești (a majority Jewish residential area, where he lived in two successive locations), and ultimately to a house a short distance away from Foişorul de Foc. Between these changes of address, he established contacts with the Symbolist and avant-garde society of Bucharest: a personal friend of graphic artist Iosif Ross, he formed an informal avant-garde circle of his own, attended by writers F. Brunea-Fox, Ion Călugăru, Henri Gad, Sașa Pană, Claude Sernet-Cosma and Ilarie Voronca, as well as by artist-director Armand Pascal (who, in 1920, married Lina Fundoianu). Pană would later note his dominant status within the group, describing him as the "stooping green-eyed youth from Iași, the standard-bearer of the iconoclasts and rebels of the new generation".

The group was occasionally joined by other friends, among them Millian and painter Nicolae Tonitza. In addition, Fondane and Călugăru frequented the artistic and literary club established by the controversial Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești, a cultural promoter and political militant whose influence spread over several Symbolist milieus. In a 1922 piece for Rampa, he remembered Bogdan-Piteşti in ambivalent terms: "he could not stand moral elevation. [...] He was made of the greatest of joys, in the most purulent of bodies. How many generations of ancient boyars had come to pass, like unworthy dung, for this singular earth to be generated?"

Pressed on by his family and the prospects of financial security, Fondane contemplated becoming a lawyer. Having passed his baccalaureate examination in Bucharest, he was, according to his own account, a registered student at the University of Iași Law School, obtaining a graduation certificate but prevented from becoming a licentiate by the opposition of faculty member A. C. Cuza, the antisemitic political figure. According to a recollection of poet Adrian Maniu, Fondane again worked as a fact checker for some months after his arrival to the capital. His activity as a journalist also allowed him to interview Arnold Davidovich Margolin, statesman of the defunct Ukrainian People's Republic, with whom he discussed the fate of Ukrainian Jews before and after the Soviet Russian takeover.

Sburătorul, Contimporanul, Insula

Over the following years, he restarted his career in the press, contributing to various nationally circulated newspapers: Adevărul, Adevărul Literar şi Artistic, Cuvântul Liber, Mântuirea, etc. The main topics of his interest were literary reviews, essays reviewing the contribution of Romanian and French authors, various art chronicles, and opinion pieces on social or cultural issues. A special case was his collaboration with Mântuirea, a Zionist periodical founded by Zissu, where, between August and October 1919, he published his studies collection Iudaism şi elenism ("Judaism and Hellenism"). These pieces, alternating with similar articles by Galaction, showed how the young man's views in cultural anthropology had been shaped by his relationship with Gropper (with whom he nevertheless severed all contacts by 1920).

Fondane also renewed his collaboration with Rampa. He and another contributor to the magazine, journalist Tudor Teodorescu-Braniște, carried out a debate in the magazine's pages: Fondane's articles defended Romanian Symbolism against criticism from Teodorescu-Branişte, and offered glimpse into his personal interpretation of Symbolist attitudes. One piece he wrote in 1919, titled Noi, simboliștii ("Us Symbolists") stated his proud affiliation to the current (primarily defined by him as an artistic transposition of eternal idealism), and comprised the slogan: "We are too many not to be strong, and too few not to be intelligent." In May 1920, another of his Rampa contributions spoke out against Octavian Goga, Culture Minister of the Alexandru Averescu executive, who contemplated sacking George Bacovia from his office of clerk. The same year, Lumea Evree published his verse drama fragment Monologul lui Baltazar ("Belshazzar's Soliloquy").

Around the time of his relocation to Bucharest, Fondane first met the moderate modernist critic Eugen Lovinescu, and afterward became both an affiliate of Lovinescu's circle and a contributor to his literary review Sburătorul. Among his first contributions there was a retrospective coverage of the boxing match between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier, which comprised his reflections on the mythical power of sport and the clash of cultures. Although a Sburătorist, he was still in contact with Galaction and the left-wing circles. In June 1921, Galaction paid homage to "the daring Benjamin" in an article for Adevărul Literar şi Artistic, calling attention to Fondane's "overwhelming originality."

A year later, Fondane was employed by Vinea's new venue, the prestigious modernist venue Contimporanul. Having debuted in its first issue with a comment on Romanian translation projects (Ferestre spre Occident, "Windows on the Occident"), he was later assigned the theatrical column. Fondane's work was again featured in Flacăra magazine (at the time under Minulescu's direction): the poem Ce simplu ("How Simple") and the essay Istoria Ideii ("The History of the Idea") were both published there in 1922. The same year, with assistance from fellow novelist Felix Aderca, Fondane grouped his earlier essays on French literature as Imagini şi cărţi din Franţa ("Images and Books from France"), published by Editura Socec company. The book included what was probably the first Romanian study of Marcel Proust's contribution as a novelist. The author announced that he was planning a similar volume, grouping essays about Romanian writers, both modernists (Minulescu, Bacovia, Arghezi, Maniu, Galaction) and classics (Alexandru Odobescu, Ion Creangă, Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea, Anton Pann), but this work was not published in his lifetime.

Also in 1922, Fondane and Pascal set up the theatrical troupe Insula ("The Island"), which stated its commitment to avant-garde theater. Probably named after Minulescu's earlier Symbolist magazine, the group was likely a local replica of Jean Copeau's nonconformist productions in France. Hosted by the Maison d'Art galleries in Bucharest, the company was joined by, among others, actresses Lina Fundoianu-Pascal and Victoria Mierlescu, and director Sandu Eliad. Other participants were writers (Cocea, Pană, Zissu, Scarlat Callimachi, Mărgărita Miller Verghy, Ion Pillat) and theatrical people (George Ciprian, Marietta Sadova, Soare Z. Soare, Dida Solomon, Alice Sturdza, Ionel Ţăranu).

Although it stated its goal of revolutionizing the Romanian repertoire (a goal published as an art manifesto in Contimporanul), Insula produced mostly conventional Symbolist and Neoclassical plays: its inaugural shows included Legenda funigeilor ("Gossamer Legend") by Ștefan Octavian Iosif and Dimitrie Anghel, one of Lord Dunsany's Five Plays and (in Fondane's own translation) Molière's Le Médecin volant. Probably aiming to enrich this program with samples of Yiddish drama, Fondane began, but never finished, a translation of S. Ansky's The Dybbuk. The troupe ceased its activity in 1923, partly because of significant financial difficulties, and partly because of a rise in antisemitic activities, which put its Jewish performers at risk. For a while, Insula survived as a conference group, hosting modernist lectures on classical Romanian literature—with the participation of Symbolist and post-Symbolist authors such as Aderca, Arghezi, Millian, Pillat, Vinea, N. Davidescu, Perpessicius, and Fondane himself. He was at the time working on his own play, Filoctet ("Philoctetes", later finished as Philoctète).

Move to France

In 1923, Benjamin Fondane eventually left Romania for France, spurred on by the need to prove himself within a different cultural context. He was at the time interested in the success of Dada, an avant-garde movement launched abroad by the Romanian-born author Tristan Tzara, in collaboration with several others. Not dissuaded by the fact that his sister and brother-in-law (the Pascals) had returned impoverished from an extended stay in Paris, Fondane crossed Europe by train and partly by foot.

The writer (who adopted his Francized name shortly after leaving his native country) was eventually joined there by the Pascals. The three of them continued to lead a bohemian and at times precarious existence, discussed in Fondane's correspondence with Romanian novelist Liviu Rebreanu, and described by researcher Ana-Maria Tomescu as "humiliating poverty". The poet acquired some sources of income from his contacts in Romania: in exchange for his contribution to the circulation of Romanian literature in France, he received official funds from the Culture Ministry's directorate (at the time headed by Minulescu); in addition, he published unsigned articles in various newspapers, and even relied on handouts from Romanian actress Elvira Popescu (who visited his home, as did avant-garde painter M. H. Maxy). He also translated into French Zissu's novel Amintirile unui candelabru ("The Recollections of a Chandelier"). For a while, the poet also joined his colleague Ilarie Voronca on the legal department of L'Abeille insurance company.

After a period of renting furnished rooms, Fondane accepted an offer from Jean, brother of the deceased literary theorist Remy de Gourmont, and, employed as a librarian-concierge, moved into the Gourmonts' museum property on Rue des Saints-Pères, some distance away from to the celebrated literary café Les Deux Magots. In the six years before Pascal's 1929 death, Fondane left Gourmont's house and, with his sister and brother-in-law, moved into a succession of houses (on Rue Domat, Rue Jacob, Rue Monge), before settling into a historical building once inhabited by author Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (Rue Rollin, 6). Complaining about eye trouble and exhaustion, and several times threatened with insolvency, Fondane often left Paris for the resort of Arcachon.

Claudia Millian, who was also spending time in Paris, described Fondane's new focus on studying Christian theology and Catholic thought, from Hildebert to Gourmont's own Latin mystique (it was also at this stage that the Romanian writer acquired and sent home part of Gourmont's bibliophile collection). He coupled these activities with an interest in grouping together the cultural segments of the Romanian diaspora: around 1924, he and Millian were founding members of the Society of Romanian Writers in Paris, presided upon by the aristocrat Elena Văcărescu. Meanwhile, Fondane acquired a profile on the local literary scene, and, in his personal notes, claimed to have had his works praised by novelist André Gide and philosopher Jules de Gaultier. They both were his idols: Gide's work had shaped his own contribution in the prose poem genre, while Gaultier did the same for his philosophical outlook. The self-exiled debutant was nevertheless still viewing his career with despair, describing it as languishing, and noting that there was a chance of him failing to earn a solid literary reputation.

Surrealist episode

The mid-1920s brought Benjamin Fondane's affiliation with Surrealism, the post-Dada avant-garde current centered in Paris. Fondane also rallied with Belgian Surrealist composers E. L. T. Mesens and André Souris (with whom he signed a manifesto on modernist music), and supported Surrealist poet-director Antonin Artaud in his efforts to set up a theater named after Alfred Jarry (which was not, however, an all-Surrealist venue). In this context, he tried to persuade the French Surrealist group to tour his native country and establish contacts with local affiliates.

By 1926, Fondane grew disenchanted with the communist alignment proposed by the main Surrealist faction and its mentor, André Breton. Writing at the time, he commented that the ideological drive could prove fatal: "Perhaps never again will [a poet] recover that absolute freedom that he had in the bourgeois republic." A few years later, the Romanian writer expressed his support for the anti-Breton dissidents of Le Grand Jeu magazine, and was a witness at the 1930 riot which opposed the two factions. His anti-communist discourse was again aired in 1932: commenting on indictment of Surrealist poet Louis Aragon for communist texts (read by the authorities as instigation to murder), Fondane stated that he did believe Aragon's case was covered by the freedom of speech. His ideas also brought him into conflict with Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, who was moving away from an avant-garde background and into the realm of far right ideas. By the early 1930s, Fondane was in contact with the mainstream modernist Jacques Rivière and his Nouvelle Revue Française circle.

In 1928, his own collaboration with the Surrealists took shape as the book Trois scenarii: ciné-poèmes ("Three Scenarios: Cine-poems"), published by Documents internationaux de l'esprt nouveau collection, with artwork by American photographer Man Ray and Romanian painter Alexandru Brătăşanu (one of his other contacts in the French Surrealist photographers' group was Eli Lotar, the illegitimate son of Arghezi and nephew of Zissu). The "cine-poems" were intentionally conceived as unfilmable screenplays, in what was his personal statement about artistic compromise between experimental film and the emerging worldwide film industry. The book notably comprised his verdict about cinema being "the only art that was never classical."

Philosophical debut

With time, Fondane became a contributor to newspapers or literary journals in France, Belgium, and Switzerland: a regular presence in Cahiers du Sud of Carcassonne, he had his work featured in the Surrealist press (Discontinuité, Le Phare de Neuilly, Bifur), as well as in Le Courrier des Poètes, Le Journal des Poètes, Romain Rolland's Europe, Paul Valéry's Commerce etc. In addition, Fondane's research was hosted by specialized venues such as Revue Philosophique, Schweizer Annalen and Carlo Suarès' Cahiers de l'Étoile. After a long period of indecision, the Romanian poet became a dedicated follower of Lev Shestov, a Russian-born existentialist thinker whose ideas about the eternal opposition between faith and reason he expanded upon in later texts. According to intellectual historian Samuel Moyn, Fondane was, with Rachel Bespaloff, one of the "most significant and devoted of Shestov's followers". In 1929, as a frequenter of Shestov's circle, Fondane also met Argentinian female author Victoria Ocampo, who became his close friend (after 1931, he became a contributor to her modernist review, Sur). Fondane's essays were more frequently than before philosophical in nature: Europe published his tribute Shestov (January 1929) and his comments of Edmund Husserl's phenomenology, which included his own critique of rationalism (June 1930).

Invited (on Ocampo's initiative) by the Amigos del Arte society of Buenos Aires, Fondane left for Argentina and Uruguay in summer 1929. The object of his visit was promoting French cinema with a set of lectures in Buenos Aires, Montevideo and other cities (as he later stated in a Rampa interview with Sarina Cassvan-Pas, he introduced South Americans to the work of Germaine Dulac, Luis Buñuel and Henri Gad). In this context, Fondane met essayist Eduardo Mallea, who invited him to contribute in La Nación's literary supplement. His other activities there included conferencing on Shestov at the University of Buenos Aires and publishing articles on several subjects (from Shestov's philosophy to the poems of Tzara), but the fees received in return were, in his own account, too small to cover the cost of decent living.

In October 1929, Fondane was back in Paris, where he focused on translating and popularizing some of Romanian literature's milestone texts, from Mihai Eminescu's Sărmanul Dionis to the poetry of Ion Barbu, Minulescu, Arghezi and Bacovia. In the same context, the expatriate writer helped introduce Romanians to some of the new European tendencies, becoming, in the words of literary historian Paul Cernat, "the first important promoter of French Surrealism in Romanian culture."

Integral and unu

In the mid-1920s, Fondane and painter János Mattis-Teutsch joined the external editorial board of Integral magazine, an avant-garde tribune published in Bucharest by Ion Călugăru, F. Brunea-Fox and Voronca. He was assigned a permanent column, known as Fenêtres sur l'Europe/Ferestre spre Europa (French and Romanian for "Windows on Europe"). With Barbu Florian, Fondane became a leading film reviewer for the magazine, pursuing his agenda in favor of non-commercial and "pure" films (such as René Clair's Entr'acte), and praising Charlie Chaplin for his lyricism, but later making some concessions to talkies and the regular Hollywood films. Exploring what he defined as "the great ballet of contemporary French poetry", Fondane also published individual notes on writers Aragon, Jean Cocteau, Joseph Delteil, Paul Éluard and Pierre Reverdy. In 1927, Integral also hosted one of Fondane's replies to the communist Surrealists in France, as Le surréalisme et la révolution ("Surrealism and Revolution").

He also came into contact with unu, the Surrealist venue of Bucharest, which was edited by several of his avant-garde friends at home. His contributions there included a text on Tzara's post-Dada works, which he analyzed as Valéry-like "pure poetry". In December 1928, unu published some of Fondane's messages home, as Scrisori pierdute ("Lost Letters"). Between 1931 and 1934, Fondane was in regular correspondence with the unu writers, in particular Stephan Roll, F. Brunea-Fox and Saşa Pană, being informed about their conflict with Voronca (attacked as a betrayer of the avant-garde) and witnessing from afar the eventual implosion of Romanian Surrealism on the model of French groups. In such dialogues, Roll complains about right-wing political censorship in Romania, and speaks in some detail about his own conversion to Marxism.