Lillian Hellman is a Actor, Scriptwriter and Additional Dialogue American born on 20 june 1905 at New Orleans (USA)

Lillian Florence "Lilly" Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American author of plays, screenplays, and memoirs and throughout her life, was linked with many left-wing political causes.

Lillian Hellman was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, into a Jewish family. Her mother was Julia Newhouse of Demopolis, Alabama and her father was Max Hellman, a New Orleans shoe salesman. Julia Newhouse's parents were Sophie Marx, of a successful banking family, and Leonard Newhouse, a Demopolis liquor dealer. During most of her childhood she spent half of each year in New Orleans, in a boarding home run by her aunts, and the other half in New York City. She studied for two years at New York University and then took several courses at Columbia University.

On December 31, 1925, Hellman married Arthur Kober, a playwright and press agent, although they often lived apart. In 1929, she traveled around Europe for a time and settled in Bonn to continue her education. She felt an initial attraction to a Nazi student group that advocated "a kind of socialism" until their questioning about her Jewish ties made their antisemitism clear, and she returned immediately to the United States. Years later she wrote, "Then for the first time in my life I thought about being a Jew."

Career and politics, 1930s

Beginning in 1930, for about a year she earned $50 a week as a reader for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Hollywood, writing summaries of novels and periodical literature for potential screenplays. While there she met and fell in love with mystery writer Dashiell Hammett. She divorced Kober and returned to New York City in 1932. When she met Hammett in a Hollywood restaurant, she was 24 and he was 36. They maintained their relationship off and on until his death in January 1961.

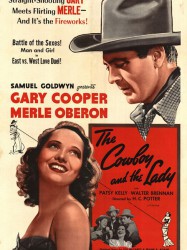

Hellman's drama, The Children's Hour, premiered on Broadway on November 24, 1934, and ran for 691 performances. It depicts a false accusation of lesbianism by a schoolgirl against two of her teachers. The falsehood is discovered, but before amends can be made one teacher is rejected by her fiancé and the other commits suicide. Following the success of The Children's Hour, Hellman returned to Hollywood as a screenwriter for Goldwyn Pictures at $2500 a week. She first collaborated on a screenplay for The Dark Angel, an earlier play and silent film. Following that film's successful release in 1935, Goldwyn purchased the rights to The Children's Hour for $35,000 while it still was running on Broadway. Hellman rewrote the play to conform to the standards of the Motion Picture Production Code, under which any mention of lesbianism was impossible. Instead, one schoolteacher is accused of having sex with the other's fiancé. It appeared in 1936 under the title, These Three. She next wrote the screenplay for Dead End, which featured the first appearance of the Dead End Kids and premiered in 1937.

In 1935, Hellman joined the struggling Screen Writers Guild, devoted herself to recruiting new members, and proved one of its most aggressive advocates. One of its key issues was the dictatorial way producers credited writers for their work, known as "screen credit". Hellman had received no recognition for some of her earlier projects, although she was the principal author of The Westerner (1934) and a principal contributor to The Melody Lingers On (1935).

In December 1936, her play Days to Come closed its Broadway run after just seven performances. In it, she portrayed a labor dispute in a small Ohio town during which the characters try to balance the competing claims of owners and workers, both represented as valid. Communist publications denounced her failure to take sides. That same month she joined several other literary figures, including Dorothy Parker and Archibald MacLeish, in forming and funding a company, Contemporary Historians, Inc., to back a film project, The Spanish Earth, to demonstrate support for the anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War.

In March 1937, Hellman joined a group of 88 U.S. public figures in signing "An Open Letter to American Liberals" that protested an effort headed by John Dewey to examine Leon Trotsky's defense against his 1936 condemnation by the Soviet Union. The letter has been viewed by some critics as a defense of Stalin's Moscow Purge Trials. It charged some of Trotsky's defenders with aiming to destabilize the Soviet Union and said that the Soviet Union "should be left to protect itself against treasonable plots as it saw fit." It asked U.S. liberals and progressives to unite with the Soviet Union against the growing fascist threat and avoid an investigation that would only fuel "the reactionary sections of the press and public" in the United States. Endorsing this view, the editors of the New Republic wrote that "there are more important questions than Trotsky's guilt". Those who signed the "Open Letter" called for a united front against fascism, that in their view required uncritical support of the Soviet Union.

In October 1937, Hellman spent a few weeks in Spain to lend her support, as other writers had, to the International Brigades of non-Spaniards who had joined the anti-Franco side in the Spanish Civil War. As bombs fell on Madrid, she broadcast a report to the U.S. on Madrid Radio. In 1989, journalist and Ernest Hemingway's third wife, Martha Gellhorn, herself in Spain at that period, disputed the account of this trip in Hellman's memoirs and claimed that Hellman waited until all witnesses were dead before describing events that never occurred. Nevertheless, Hellman had documented her trip in the New Republic in April 1938 as "A Day in Spain." Langston Hughes wrote admiringly of the radio broadcast in 1956.

Hellman was a member of the Communist Party from 1938 to 1940, by her own account written in 1952, "a most casual member. I attended very few meetings and saw and heard nothing more than people sitting around a room talking of current events or discussing the books they had read. I drifted away from the Communist Party because I seemed to be in the wrong place. My own maverick nature was no more suitable to the political left than it had been to the conservative background from which I came."

Her play The Little Foxes opened on Broadway on February 13, 1939, and ran for 410 performances.

Career and politics, 1940s

On January 9, 1940, viewing the spread of fascism in Europe and fearing similar political developments in the United States, she said at a luncheon of the American Booksellers Association:

I am a writer and I am also a Jew. I want to be quite sure that I can continue to be a writer and if I want to say that greed is bad or persecution is worse, I can do so without being branded by the malice of people who make a living by that malice. I also want to be able to go on saying that I am a Jew without being afraid of being called names or end in a prison camp or be forbidden to walk the street at night.

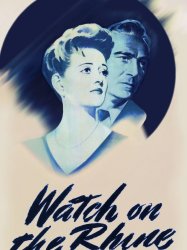

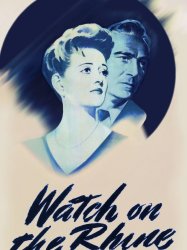

Her play Watch on the Rhine opened on Broadway on April 1, 1941, and ran for 378 performances. It won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award. She wrote the play in 1940, when its call for a united international alliance against Hitler directly contradicted the Communist position at the time, following the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939. Early in 1942, Hellman accompanied the production to Washington, D.C., for a benefit performance where she spoke with President Roosevelt. Hammett wrote the screenplay for the movie version that appeared in 1943.

In October 1941, Hellman and Ernest Hemingway co-hosted a dinner to raise money for anti-Nazi activists imprisoned in France. New York Governor Herbert Lehman agreed to participate, but withdrew because some of the sponsoring organizations, he wrote, "have long been connected with Communist activities." Hellman replied: "I do not and I did not ask the politics of any members of the committee and there is nobody who can with honesty vouch for anybody but themselves." She assured him the funds raised would be used as promised and later provided him with a detailed accounting. The next month she wrote him: "I am sure it will make you sad and ashamed as it did me to know that, of the seven resignations out of 147 sponsors, five were Jews. Of all the peoples in the world, I think, we should be the last to hold back help, on any grounds, from those who fought for us."

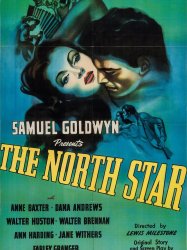

In 1942, Hellman received an Academy Award nomination for her screenplay for the film version of The Little Foxes. Two years later, she received another nomination for her screenplay for The North Star, the only original screenplay of her career. She objected to the film's production numbers that, she said, turned a village festival into "an extended opera bouffe peopled by musical comedy characters," but still told the New York Times that it was "a valuable and true picture which tells a good deal of the truth about fascism." To establish the difference between her screenplay and the film, Hellman published her screenplay in the fall of 1943.

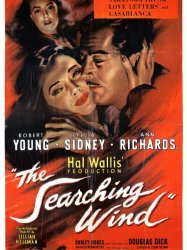

In April 1944, Hellman's The Searching Wind opened on Broadway. Her third World War II project, it tells the story of an ambassador whose indecisive relations with his wife and mistress mirror the vacillation and appeasement of his professional life. She wrote the screenplay for the film version that appeared two years later. Both versions depicted the ambassador's feckless response to anti-Semitism. The conservative press noted that the play reflected none of Hellman's pro-Soviet views, and the communist response to the play was negative.

Hellman's applications for a passport to travel to England in April 1943 and May 1944 were both denied because government authorities considered her "an active Communist," though in 1944 the head of the Passport Division of the Department of State, Ruth Shipley, cited "the present military situation" as the reason. In August 1944, she received a passport, indicative of government approval, for travel to Russia on a goodwill mission as a guest of VOKS, the Soviet agency that handled cultural exchanges. During her visit from November 5, 1944, to January 18, 1945, she began an affair with John F. Melby, a foreign service officer, that continued as an intermittent affair for years and as a friendship for the rest of her life.

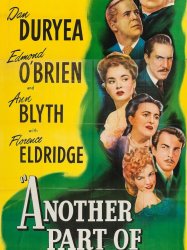

In May 1946, the National Institute of Arts and Letters made Hellman a member. In November of that year, her play Another Part of the Forest premiered, directed by Hellman. It presented the same characters twenty years younger than they had appeared in The Little Foxes. A film version to which Hellman did not contribute followed in 1948.

In 1947, Columbia Pictures offered Hellman a multi-year contract, which she refused because the contract included a loyalty clause that she viewed as an infringement on her rights of free speech and association. It required her to sign a statement that she had never been a member of the Communist Party and would not associate with radicals or subversives, which would have required her to end her life with Hammett. Shortly thereafter, William Wyler told her he was unable to hire her to work on a film because she was blacklisted.

In November 1947, the leaders of the motion picture industry decided to deny employment to anyone who refused to answer questions posed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Following the Hollywood Ten's defiance of the committee, Hellman wrote an editorial in the December issue of Screen Writer, the publication of the Screen Writers Guild. Titled "The Judas Goats," it mocked the committee and derided the producers for allowing themselves to be intimidated. It said in part:

It was a week of turning the head in shame; of the horror of seeing politicians make the honorable institution of Congress into a honky tonk show; of listening to craven men lie and tattle, pushing each other in their efforts to lick the boots of their vilifiers; publicly trying to wreck the lives, not of strangers, mind you, but of men with whom they have worked and eaten and played, and made millions....

But why this particular industry, these particular people? Has it anything to do with Communism? Of course not. There has never been a single line or word of Communism in any American picture at any time. There has never or seldom been ideas of any kind. Naturally, men scared to make pictures about the American Negro, men who only in the last year have allowed the word Jew to be spoken in a picture, men who took more than ten years to make an anti-Fascist picture, those are frightened men and you pick frightened men to frighten first. Judas goats; they'll lead the others, maybe, to the slaughter for you....

They frighten mighty easy, and they talk mighty bad....I suggest the rest of us don't frighten so easy. It's still not un-American to fight the enemies of one's country. Let's fight.

Melby and Hellman corresponded regularly in the years following World War II while he held State Department assignments overseas. Their political views diverged as he came to advocate containment of communism while she was unwilling to hear criticism of the Soviet Union. They became, in one historian's view, "political strangers, occasional lovers, and mostly friends." Melby particularly objected to her support for Henry Wallace in the 1948 presidential election.

In 1949 she adapted Emmanuel Roblès' French-language play, Montserrat, for Broadway, where it opened on October 29. Again, Hellman directed it.

Career and politics, 1950s

The play that is recognized by critics and judged by Hellman as her best, The Autumn Garden, premiered in 1951.

“

I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions...

”

—Lillian Hellman, May 19, 1952

In 1952 Hellman was called to testify before HUAC, which had heard testimony that she had attended Communist Party meetings in 1937. She initially drafted a statement that said her two-year membership in the Communist Party had ended in 1940, but she did not condemn the party nor express regret for her participation in it. Her attorney, Joseph Rauh, opposed her admission of membership on technical grounds because she had attended meetings, but never formally become a party member. He warned that the committee and the public would expect her to take a strong anti-communist stand to atone for her political past, but she refused to apologize or denounce the party. Faced with Hellman's position, Rauh devised a strategy that produced favorable press coverage and allowed her to avoid the stigma of being labeled a "Fifth Amendment Communist". On May 19, 1952, Hellman authored a letter to HUAC that one historian has described as "written not to persuade the Committee, but to shape press coverage." In it she explained her willingness to testify only about herself and that she did not want to claim her rights under the Fifth Amendment–"I am ready and willing to testify before the representatives of our Government as to my own actions, regardless of any risks or consequences to myself." She wrote that she found the legal requirement that she testify about others if she wanted to speak about her own actions "difficult for a layman to understand." Rauh had the letter delivered to the HUAC's chairman Rep. John S. Wood on Monday.

In public testimony before HUAC on Tuesday, May 21, 1952, Hellman answered preliminary questions about her background. When asked about attending a specific meeting at the home of Hollywood screenwriter Martin Berkeley, she refuse to respond, claiming her rights under the Fifth Amendment and she referred the committee to her letter by way of explanation. The Committee responded that it had considered and rejected her request to be allowed to testify only about herself and entered her letter into the record. Hellman answered only one additional question: she denied she had ever belonged to the Communist Party. She cited the Fifth Amendment in response to several more questions and the committee dismissed her. Historian John Earl Haynes credits both Rauh's "clever tactics" and Hellman's "sense of the dramatic" for what followed the conclusion of Hellman's testimony. As the committee moved on to other business, Rauh released to the press copies of her letter to HUAC. Committee members, unprepared for close questioning about Hellman's stance, offered only offhand comments. The press reported Hellman's statement at length, its language crafted to overshadow the comments of the HUAC members. She wrote in part:

But there is one principle that I do understand. I am not willing, now or in the future, to bring bad trouble to people who, in my past association with them, were completely innocent of any talk or any action that was disloyal or subversive. I do not like subversion or disloyalty in any form and if I had ever seen any I would have considered it my duty to have reported it to the proper authorities. But to hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions, even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have no comfortable place in any political group.

I was raised in an old-fashioned American tradition and there were certain homely things that were taught to me: to try to tell the truth, not to bear false witness, not to harm my neighbour, to be loyal to my country, and so on. In general, I respected these ideals of Christian honor and did as well as I knew how. It is my belief that you will agree with these simple rules of human decency and will not expect me to violate the good American tradition from which they spring. I would therefore like to come before you and speak of myself.

Reaction divided along political lines. Murray Kempton, a longtime critic of her sympathy for communist causes, praised her: "It is enough that she has reached into her conscience for an act based on something more than the material or the tactical...she has chosen to act like a lady." The FBI increased its surveillance of her travel and her mail.

In the early 1950s, at the height of anti-communist fervor in the United States, the state department investigated whether Melby posed a security risk. In April 1952, the department stated its one formal charge against him: "that during the period 1945 to date, you have maintained an association with one, Lillian Hellman, reliably reported to be a member of the Communist Party," based on testimony from unidentified informants. When Melby appeared before the department's Loyalty Security Board, he was not allowed to contest Hellman's Communist Party affiliation or learn who informed against her, but only to present his understanding of her politics and the nature of his relationship with her, including the occasional renewal of their physical relationship. He said he had no plans to renew their friendship, but never promised to avoid contact with her. In the course of a series of appeals, Hellman testified before the Loyalty Security Board on his behalf. She offered to answer questions about her political views and associations, but the board only allowed her to describe her relationship with Melby. She testified that she had many longstanding friendships with people of different political views and that political sympathy was not a part of those relationships. She described how her relationship with Melby changed over time and how their sexual relationship was briefly renewed in 1950 after a long hiatus: "The relationship obviously at this point was neither one thing nor the other: it was neither over nor was it not over." She said that:

...to make it black and white would be the lie it never has been, nor do I think many other relations ever are. I don't think it is as much a mystery as perhaps it looks. It has been a...completely personal relationship of two people who once past being in love also happen to be very devoted to each other and very respectful of one another, and who I think in any other time besides our own would not be open to question of the complete innocence of and the complete morality, if I may say so, of people who were once in love and who have come out with respect and devotion to one another.

The State Department dismissed Melby on April 22, 1953. As was its practice, the board gave no reason for its decision.

In 1954, Hellman declined when asked to adapt Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl (1952) for the stage. According to writer and director Garson Kanin, she said that the diary was "a great historical work which will probably live forever, but I couldn't be more wrong as the adapter. If I did this it would run one night because it would be deeply depressing. You need someone who has a much lighter touch." She recommended her friends, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

Hellman made an English-language adaption of Jean Anouilh's play, L'Alouette, based on the trial of Joan of Arc, called The Lark. Leonard Bernstein composed incidental music for the first production, which opened on Broadway on November 17, 1955. Hellman edited a collection of Chekhov's correspondence that appeared in 1955 as The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov.

Following the success of The Lark, Hellman conceived of another play with incidental music, based on Voltaire's Candide. Bernstein convinced her to develop it as a comic operetta with a much more substantial musical component. She wrote the spoken dialogue, which many others then worked on, and wrote some lyrics as well for what became the often-revived, Candide. Hellman hated the collaboration and revisions on deadline that Candide required: "I went to pieces when something had to be done quickly, because someone didn't like something, and there was no proper time to think it out...I realized that I panicked under conditions I wasn't accustomed to."

Career and politics, 1960s

Her play Toys in the Attic opened on Broadway on February 25, 1960, and ran for 464 performances. It received a Tony Award nomination for Best Play. In this family drama set in New Orleans, money, marital infidelity, and revenge end in a woman's disfigurement. Hellman had no hand in the screenplay, which altered the drama's tone and exaggerated the characterizations, and the resulting film received bad reviews.

A second film version of The Children's Hour, less successful both with critics and at the box office, appeared in 1961 under that title, but Hellman played no role in the screenplay, having withdrawn from the project following Hammett's death in 1961. In 1961, Brandeis University awarded her its Creative Arts Medal for outstanding lifetime achievement and the women's division of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University gave her its Achievement Award. The following year, in December 1962, Hellman was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and inducted at a May 1963 ceremony.

Another play, My Mother, My Father, and Me, proved unsuccessful when it was staged in March 1963. It closed after 17 performances. Hellman adapted it from Burt Blechman's novel How Much?

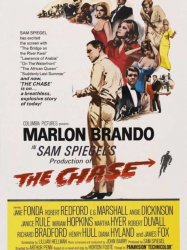

Hellman wrote another screenplay in 1965 for The Chase starring Marlon Brando based on a play and novel by Horton Foote. Though Hellman received sole credit for the screenplay, she worked from an earlier treatment, and director Sam Spiegel made additional changes and altered the sequence of scenes. In 1966, she edited a collection of Hammett's stories, The Big Knockover. Her introductory profile of Hammett was her first exercise in memoir writing.

Hellman wrote a reminiscence of gulag-survivor Lev Kopelev, husband of her translator in Russia during 1944, to serve as the introduction to his anti-Stalinist memoirs, To Be Preserved Forever, which appeared in 1976. In February 1980, she, John Hersey, and Norman Mailer wrote to Soviet authorities to protest retribution against Kopelev for his defense of Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov.

Hellman was a long-time friend of author Dorothy Parker and served as her literary executor after her death in 1967.

Hellman published her first volume of memoirs, An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir, in 1969. For it she won the U.S. National Book Award in category Arts and Letters.

Career and politics, 1970s

In the early 1970s, Hellman taught writing for short periods at the University of California, Berkeley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Hunter College in New York City.

Her second volume of memoirs, Pentimento: A Book of Portraits, appeared in 1973. In an interview at the time, Hellman described the difficulty of writing about the 1950s:

I wasn't as shocked by McCarthy as by all the people who took no stand at all....I don't remember one large figure coming to anybody's aid. It's funny. Bitter funny. Black funny. And so often something else–in the case of Clifford Odets, for example, heart-breaking funny. I suppose I've come out frightened, thoroughly frightened of liberals. Most radicals of the time were comic but the liberals were frightening.

Hellman published her third volume of memoirs, Scoundrel Time, in 1976.

In 1976, Hellman posed in a fur coat for the Blackglama national advertising campaign "What Becomes a Legend Most?". In August of that year she was awarded the prestigious Edward MacDowell Medal for her contribution to literature. In October, she received the Paul Robeson Award from Actors' Equity.

In 1976, Hellman's publisher, Little Brown, canceled its contract to publish a book of Diana Trilling's essays because Trilling refused to delete four passages critical of Hellman. When Trilling's collection appeared in 1977, a sympathetic critic in the New York Times preferred the "simple confession of error" Hellman made in Scoundrel Time for her "acquiescence in Stalinism" to Trilling's excuses for her own behavior during the McCarthy period.

Hellman presented the Academy Award for Best Documentary Film at a ceremony on March 28, 1977. Greeted by a standing ovation, she said:

I was once upon a time a respectable member of this community. Respectable didn't necessarily mean more than I took a daily bath when I was sober, didn't spit except when I meant to, and mispronounced a few words of fancy French. Then suddenly, even before Senator Joe McCarthy reached for that rusty, poisoned ax, I and many others were no longer acceptable to the owners of this industry....[T]hey confronted the wild charges of Joe McCarthy with a force and courage of a bowl of mashed potatoes. I have no regrets for that period. Maybe you never do when you survive, but I have a mischievous pleasure in being restored to respectability, understanding full well that the younger generation who asked me here tonight meant more by that invitation than my name or my history.

The 1977 Oscar-winning film Julia was based on the "Julia" chapter of Pentimento. On June 30, 1976, as the film was going into production, Hellman wrote about the screenplay to its producer:

This is not a work of fiction and certain laws have to be followed for that reason...Your major difficulty to me is the treatment of Lillian as the leading character. The reason is simple: no matter what she does in this story–and I do not deny the danger I was in when I took the money into Germany–my role was passive. And nobody and nothing can change that unless you write a fictional and different story...Isn't it necessary to know that I am a Jew? That, of course, is what mainly made the danger.

In a 1979 television interview, author Mary McCarthy, long Hellman's political adversary and the object of her negative literary judgment, said of Hellman that "every word she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the'." Hellman responded by filing a US$2,500,000 defamation suit against McCarthy, interviewer Dick Cavett, and PBS. McCarthy in turn produced evidence she said proved that Hellman had lied in some accounts of her life. Cavett said he sympathized more with McCarthy than Hellman in the lawsuit, but "everybody lost" as a result of it. Norman Mailer attempted unsuccessfully to mediate the dispute through an open letter he published in the New York Times. At the time of her death, Hellman was still in litigation with Mary McCarthy, and Hellman's executors dropped the suit.

Last years

In 1980, Hellman published a short novel, Maybe: A Story. Though presented as fiction, Hellman, Hammett, and other nonfictional people appeared as characters. It received a mixed reception and was sometimes read as another installment of Hellman's memoirs. Hellman's editor wrote to the New York Times to question a reviewer's attempt to check the facts in the novel. He described it as a work of fiction whose characters misremember and dissemble.

In 1983, New York psychiatrist Muriel Gardiner claimed that she was the basis for the title character in Julia and that she had never known Hellman. Hellman denied that the character was based on Gardiner. Because the events Hellman described matched Gardiner's account of her life and Gardiner's family was closely tied to Hellman's attorney, some believe that Hellman appropriated Gardiner's story without attribution.

Hellman died on June 30, 1984, at age 79 from a heart attack at her home on Martha's Vineyard.

Institutions that awarded Hellman honorary degrees include Brandeis University (1955), Wheaton College (1960), Mt. Holyoke College (1966), Smith College (1974), Yale University (1974), and Columbia University (1976).

Hellman's papers are held at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Human Rights Watch administers the Hellman/Hammett grant program named for the two writers.

(1977)

(1977)

(Book) (1935)

(1935)

(Scriptwriter) (1943)

(1943)

(Theatre Play) (1940)

(1940)

(Scriptwriter) (1938)

(1938)

(Additional Writing)

Source : Wikidata

Lillian Hellman

- Infos

- Photos

- Best films

- Family

- Characters

- Awards

Birth name Lillian Florence Hellman

Nationality USA

Birth 20 june 1905 at New Orleans (USA)

Death 30 june 1984 (at 79 years) at Massachusetts (USA)

Awards National Book Award

Nationality USA

Birth 20 june 1905 at New Orleans (USA)

Death 30 june 1984 (at 79 years) at Massachusetts (USA)

Awards National Book Award

Biography

Early life and marriageLillian Hellman was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, into a Jewish family. Her mother was Julia Newhouse of Demopolis, Alabama and her father was Max Hellman, a New Orleans shoe salesman. Julia Newhouse's parents were Sophie Marx, of a successful banking family, and Leonard Newhouse, a Demopolis liquor dealer. During most of her childhood she spent half of each year in New Orleans, in a boarding home run by her aunts, and the other half in New York City. She studied for two years at New York University and then took several courses at Columbia University.

On December 31, 1925, Hellman married Arthur Kober, a playwright and press agent, although they often lived apart. In 1929, she traveled around Europe for a time and settled in Bonn to continue her education. She felt an initial attraction to a Nazi student group that advocated "a kind of socialism" until their questioning about her Jewish ties made their antisemitism clear, and she returned immediately to the United States. Years later she wrote, "Then for the first time in my life I thought about being a Jew."

Career and politics, 1930s

Beginning in 1930, for about a year she earned $50 a week as a reader for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Hollywood, writing summaries of novels and periodical literature for potential screenplays. While there she met and fell in love with mystery writer Dashiell Hammett. She divorced Kober and returned to New York City in 1932. When she met Hammett in a Hollywood restaurant, she was 24 and he was 36. They maintained their relationship off and on until his death in January 1961.

Hellman's drama, The Children's Hour, premiered on Broadway on November 24, 1934, and ran for 691 performances. It depicts a false accusation of lesbianism by a schoolgirl against two of her teachers. The falsehood is discovered, but before amends can be made one teacher is rejected by her fiancé and the other commits suicide. Following the success of The Children's Hour, Hellman returned to Hollywood as a screenwriter for Goldwyn Pictures at $2500 a week. She first collaborated on a screenplay for The Dark Angel, an earlier play and silent film. Following that film's successful release in 1935, Goldwyn purchased the rights to The Children's Hour for $35,000 while it still was running on Broadway. Hellman rewrote the play to conform to the standards of the Motion Picture Production Code, under which any mention of lesbianism was impossible. Instead, one schoolteacher is accused of having sex with the other's fiancé. It appeared in 1936 under the title, These Three. She next wrote the screenplay for Dead End, which featured the first appearance of the Dead End Kids and premiered in 1937.

In 1935, Hellman joined the struggling Screen Writers Guild, devoted herself to recruiting new members, and proved one of its most aggressive advocates. One of its key issues was the dictatorial way producers credited writers for their work, known as "screen credit". Hellman had received no recognition for some of her earlier projects, although she was the principal author of The Westerner (1934) and a principal contributor to The Melody Lingers On (1935).

In December 1936, her play Days to Come closed its Broadway run after just seven performances. In it, she portrayed a labor dispute in a small Ohio town during which the characters try to balance the competing claims of owners and workers, both represented as valid. Communist publications denounced her failure to take sides. That same month she joined several other literary figures, including Dorothy Parker and Archibald MacLeish, in forming and funding a company, Contemporary Historians, Inc., to back a film project, The Spanish Earth, to demonstrate support for the anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War.

In March 1937, Hellman joined a group of 88 U.S. public figures in signing "An Open Letter to American Liberals" that protested an effort headed by John Dewey to examine Leon Trotsky's defense against his 1936 condemnation by the Soviet Union. The letter has been viewed by some critics as a defense of Stalin's Moscow Purge Trials. It charged some of Trotsky's defenders with aiming to destabilize the Soviet Union and said that the Soviet Union "should be left to protect itself against treasonable plots as it saw fit." It asked U.S. liberals and progressives to unite with the Soviet Union against the growing fascist threat and avoid an investigation that would only fuel "the reactionary sections of the press and public" in the United States. Endorsing this view, the editors of the New Republic wrote that "there are more important questions than Trotsky's guilt". Those who signed the "Open Letter" called for a united front against fascism, that in their view required uncritical support of the Soviet Union.

In October 1937, Hellman spent a few weeks in Spain to lend her support, as other writers had, to the International Brigades of non-Spaniards who had joined the anti-Franco side in the Spanish Civil War. As bombs fell on Madrid, she broadcast a report to the U.S. on Madrid Radio. In 1989, journalist and Ernest Hemingway's third wife, Martha Gellhorn, herself in Spain at that period, disputed the account of this trip in Hellman's memoirs and claimed that Hellman waited until all witnesses were dead before describing events that never occurred. Nevertheless, Hellman had documented her trip in the New Republic in April 1938 as "A Day in Spain." Langston Hughes wrote admiringly of the radio broadcast in 1956.

Hellman was a member of the Communist Party from 1938 to 1940, by her own account written in 1952, "a most casual member. I attended very few meetings and saw and heard nothing more than people sitting around a room talking of current events or discussing the books they had read. I drifted away from the Communist Party because I seemed to be in the wrong place. My own maverick nature was no more suitable to the political left than it had been to the conservative background from which I came."

Her play The Little Foxes opened on Broadway on February 13, 1939, and ran for 410 performances.

Career and politics, 1940s

On January 9, 1940, viewing the spread of fascism in Europe and fearing similar political developments in the United States, she said at a luncheon of the American Booksellers Association:

I am a writer and I am also a Jew. I want to be quite sure that I can continue to be a writer and if I want to say that greed is bad or persecution is worse, I can do so without being branded by the malice of people who make a living by that malice. I also want to be able to go on saying that I am a Jew without being afraid of being called names or end in a prison camp or be forbidden to walk the street at night.

Her play Watch on the Rhine opened on Broadway on April 1, 1941, and ran for 378 performances. It won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award. She wrote the play in 1940, when its call for a united international alliance against Hitler directly contradicted the Communist position at the time, following the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939. Early in 1942, Hellman accompanied the production to Washington, D.C., for a benefit performance where she spoke with President Roosevelt. Hammett wrote the screenplay for the movie version that appeared in 1943.

In October 1941, Hellman and Ernest Hemingway co-hosted a dinner to raise money for anti-Nazi activists imprisoned in France. New York Governor Herbert Lehman agreed to participate, but withdrew because some of the sponsoring organizations, he wrote, "have long been connected with Communist activities." Hellman replied: "I do not and I did not ask the politics of any members of the committee and there is nobody who can with honesty vouch for anybody but themselves." She assured him the funds raised would be used as promised and later provided him with a detailed accounting. The next month she wrote him: "I am sure it will make you sad and ashamed as it did me to know that, of the seven resignations out of 147 sponsors, five were Jews. Of all the peoples in the world, I think, we should be the last to hold back help, on any grounds, from those who fought for us."

In 1942, Hellman received an Academy Award nomination for her screenplay for the film version of The Little Foxes. Two years later, she received another nomination for her screenplay for The North Star, the only original screenplay of her career. She objected to the film's production numbers that, she said, turned a village festival into "an extended opera bouffe peopled by musical comedy characters," but still told the New York Times that it was "a valuable and true picture which tells a good deal of the truth about fascism." To establish the difference between her screenplay and the film, Hellman published her screenplay in the fall of 1943.

In April 1944, Hellman's The Searching Wind opened on Broadway. Her third World War II project, it tells the story of an ambassador whose indecisive relations with his wife and mistress mirror the vacillation and appeasement of his professional life. She wrote the screenplay for the film version that appeared two years later. Both versions depicted the ambassador's feckless response to anti-Semitism. The conservative press noted that the play reflected none of Hellman's pro-Soviet views, and the communist response to the play was negative.

Hellman's applications for a passport to travel to England in April 1943 and May 1944 were both denied because government authorities considered her "an active Communist," though in 1944 the head of the Passport Division of the Department of State, Ruth Shipley, cited "the present military situation" as the reason. In August 1944, she received a passport, indicative of government approval, for travel to Russia on a goodwill mission as a guest of VOKS, the Soviet agency that handled cultural exchanges. During her visit from November 5, 1944, to January 18, 1945, she began an affair with John F. Melby, a foreign service officer, that continued as an intermittent affair for years and as a friendship for the rest of her life.

In May 1946, the National Institute of Arts and Letters made Hellman a member. In November of that year, her play Another Part of the Forest premiered, directed by Hellman. It presented the same characters twenty years younger than they had appeared in The Little Foxes. A film version to which Hellman did not contribute followed in 1948.

In 1947, Columbia Pictures offered Hellman a multi-year contract, which she refused because the contract included a loyalty clause that she viewed as an infringement on her rights of free speech and association. It required her to sign a statement that she had never been a member of the Communist Party and would not associate with radicals or subversives, which would have required her to end her life with Hammett. Shortly thereafter, William Wyler told her he was unable to hire her to work on a film because she was blacklisted.

In November 1947, the leaders of the motion picture industry decided to deny employment to anyone who refused to answer questions posed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Following the Hollywood Ten's defiance of the committee, Hellman wrote an editorial in the December issue of Screen Writer, the publication of the Screen Writers Guild. Titled "The Judas Goats," it mocked the committee and derided the producers for allowing themselves to be intimidated. It said in part:

It was a week of turning the head in shame; of the horror of seeing politicians make the honorable institution of Congress into a honky tonk show; of listening to craven men lie and tattle, pushing each other in their efforts to lick the boots of their vilifiers; publicly trying to wreck the lives, not of strangers, mind you, but of men with whom they have worked and eaten and played, and made millions....

But why this particular industry, these particular people? Has it anything to do with Communism? Of course not. There has never been a single line or word of Communism in any American picture at any time. There has never or seldom been ideas of any kind. Naturally, men scared to make pictures about the American Negro, men who only in the last year have allowed the word Jew to be spoken in a picture, men who took more than ten years to make an anti-Fascist picture, those are frightened men and you pick frightened men to frighten first. Judas goats; they'll lead the others, maybe, to the slaughter for you....

They frighten mighty easy, and they talk mighty bad....I suggest the rest of us don't frighten so easy. It's still not un-American to fight the enemies of one's country. Let's fight.

Melby and Hellman corresponded regularly in the years following World War II while he held State Department assignments overseas. Their political views diverged as he came to advocate containment of communism while she was unwilling to hear criticism of the Soviet Union. They became, in one historian's view, "political strangers, occasional lovers, and mostly friends." Melby particularly objected to her support for Henry Wallace in the 1948 presidential election.

In 1949 she adapted Emmanuel Roblès' French-language play, Montserrat, for Broadway, where it opened on October 29. Again, Hellman directed it.

Career and politics, 1950s

The play that is recognized by critics and judged by Hellman as her best, The Autumn Garden, premiered in 1951.

“

I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions...

”

—Lillian Hellman, May 19, 1952

In 1952 Hellman was called to testify before HUAC, which had heard testimony that she had attended Communist Party meetings in 1937. She initially drafted a statement that said her two-year membership in the Communist Party had ended in 1940, but she did not condemn the party nor express regret for her participation in it. Her attorney, Joseph Rauh, opposed her admission of membership on technical grounds because she had attended meetings, but never formally become a party member. He warned that the committee and the public would expect her to take a strong anti-communist stand to atone for her political past, but she refused to apologize or denounce the party. Faced with Hellman's position, Rauh devised a strategy that produced favorable press coverage and allowed her to avoid the stigma of being labeled a "Fifth Amendment Communist". On May 19, 1952, Hellman authored a letter to HUAC that one historian has described as "written not to persuade the Committee, but to shape press coverage." In it she explained her willingness to testify only about herself and that she did not want to claim her rights under the Fifth Amendment–"I am ready and willing to testify before the representatives of our Government as to my own actions, regardless of any risks or consequences to myself." She wrote that she found the legal requirement that she testify about others if she wanted to speak about her own actions "difficult for a layman to understand." Rauh had the letter delivered to the HUAC's chairman Rep. John S. Wood on Monday.

In public testimony before HUAC on Tuesday, May 21, 1952, Hellman answered preliminary questions about her background. When asked about attending a specific meeting at the home of Hollywood screenwriter Martin Berkeley, she refuse to respond, claiming her rights under the Fifth Amendment and she referred the committee to her letter by way of explanation. The Committee responded that it had considered and rejected her request to be allowed to testify only about herself and entered her letter into the record. Hellman answered only one additional question: she denied she had ever belonged to the Communist Party. She cited the Fifth Amendment in response to several more questions and the committee dismissed her. Historian John Earl Haynes credits both Rauh's "clever tactics" and Hellman's "sense of the dramatic" for what followed the conclusion of Hellman's testimony. As the committee moved on to other business, Rauh released to the press copies of her letter to HUAC. Committee members, unprepared for close questioning about Hellman's stance, offered only offhand comments. The press reported Hellman's statement at length, its language crafted to overshadow the comments of the HUAC members. She wrote in part:

But there is one principle that I do understand. I am not willing, now or in the future, to bring bad trouble to people who, in my past association with them, were completely innocent of any talk or any action that was disloyal or subversive. I do not like subversion or disloyalty in any form and if I had ever seen any I would have considered it my duty to have reported it to the proper authorities. But to hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions, even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have no comfortable place in any political group.

I was raised in an old-fashioned American tradition and there were certain homely things that were taught to me: to try to tell the truth, not to bear false witness, not to harm my neighbour, to be loyal to my country, and so on. In general, I respected these ideals of Christian honor and did as well as I knew how. It is my belief that you will agree with these simple rules of human decency and will not expect me to violate the good American tradition from which they spring. I would therefore like to come before you and speak of myself.

Reaction divided along political lines. Murray Kempton, a longtime critic of her sympathy for communist causes, praised her: "It is enough that she has reached into her conscience for an act based on something more than the material or the tactical...she has chosen to act like a lady." The FBI increased its surveillance of her travel and her mail.

In the early 1950s, at the height of anti-communist fervor in the United States, the state department investigated whether Melby posed a security risk. In April 1952, the department stated its one formal charge against him: "that during the period 1945 to date, you have maintained an association with one, Lillian Hellman, reliably reported to be a member of the Communist Party," based on testimony from unidentified informants. When Melby appeared before the department's Loyalty Security Board, he was not allowed to contest Hellman's Communist Party affiliation or learn who informed against her, but only to present his understanding of her politics and the nature of his relationship with her, including the occasional renewal of their physical relationship. He said he had no plans to renew their friendship, but never promised to avoid contact with her. In the course of a series of appeals, Hellman testified before the Loyalty Security Board on his behalf. She offered to answer questions about her political views and associations, but the board only allowed her to describe her relationship with Melby. She testified that she had many longstanding friendships with people of different political views and that political sympathy was not a part of those relationships. She described how her relationship with Melby changed over time and how their sexual relationship was briefly renewed in 1950 after a long hiatus: "The relationship obviously at this point was neither one thing nor the other: it was neither over nor was it not over." She said that:

...to make it black and white would be the lie it never has been, nor do I think many other relations ever are. I don't think it is as much a mystery as perhaps it looks. It has been a...completely personal relationship of two people who once past being in love also happen to be very devoted to each other and very respectful of one another, and who I think in any other time besides our own would not be open to question of the complete innocence of and the complete morality, if I may say so, of people who were once in love and who have come out with respect and devotion to one another.

The State Department dismissed Melby on April 22, 1953. As was its practice, the board gave no reason for its decision.

In 1954, Hellman declined when asked to adapt Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl (1952) for the stage. According to writer and director Garson Kanin, she said that the diary was "a great historical work which will probably live forever, but I couldn't be more wrong as the adapter. If I did this it would run one night because it would be deeply depressing. You need someone who has a much lighter touch." She recommended her friends, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

Hellman made an English-language adaption of Jean Anouilh's play, L'Alouette, based on the trial of Joan of Arc, called The Lark. Leonard Bernstein composed incidental music for the first production, which opened on Broadway on November 17, 1955. Hellman edited a collection of Chekhov's correspondence that appeared in 1955 as The Selected Letters of Anton Chekhov.

Following the success of The Lark, Hellman conceived of another play with incidental music, based on Voltaire's Candide. Bernstein convinced her to develop it as a comic operetta with a much more substantial musical component. She wrote the spoken dialogue, which many others then worked on, and wrote some lyrics as well for what became the often-revived, Candide. Hellman hated the collaboration and revisions on deadline that Candide required: "I went to pieces when something had to be done quickly, because someone didn't like something, and there was no proper time to think it out...I realized that I panicked under conditions I wasn't accustomed to."

Career and politics, 1960s

Her play Toys in the Attic opened on Broadway on February 25, 1960, and ran for 464 performances. It received a Tony Award nomination for Best Play. In this family drama set in New Orleans, money, marital infidelity, and revenge end in a woman's disfigurement. Hellman had no hand in the screenplay, which altered the drama's tone and exaggerated the characterizations, and the resulting film received bad reviews.

A second film version of The Children's Hour, less successful both with critics and at the box office, appeared in 1961 under that title, but Hellman played no role in the screenplay, having withdrawn from the project following Hammett's death in 1961. In 1961, Brandeis University awarded her its Creative Arts Medal for outstanding lifetime achievement and the women's division of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University gave her its Achievement Award. The following year, in December 1962, Hellman was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and inducted at a May 1963 ceremony.

Another play, My Mother, My Father, and Me, proved unsuccessful when it was staged in March 1963. It closed after 17 performances. Hellman adapted it from Burt Blechman's novel How Much?

Hellman wrote another screenplay in 1965 for The Chase starring Marlon Brando based on a play and novel by Horton Foote. Though Hellman received sole credit for the screenplay, she worked from an earlier treatment, and director Sam Spiegel made additional changes and altered the sequence of scenes. In 1966, she edited a collection of Hammett's stories, The Big Knockover. Her introductory profile of Hammett was her first exercise in memoir writing.

Hellman wrote a reminiscence of gulag-survivor Lev Kopelev, husband of her translator in Russia during 1944, to serve as the introduction to his anti-Stalinist memoirs, To Be Preserved Forever, which appeared in 1976. In February 1980, she, John Hersey, and Norman Mailer wrote to Soviet authorities to protest retribution against Kopelev for his defense of Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov.

Hellman was a long-time friend of author Dorothy Parker and served as her literary executor after her death in 1967.

Hellman published her first volume of memoirs, An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir, in 1969. For it she won the U.S. National Book Award in category Arts and Letters.

Career and politics, 1970s

In the early 1970s, Hellman taught writing for short periods at the University of California, Berkeley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Hunter College in New York City.

Her second volume of memoirs, Pentimento: A Book of Portraits, appeared in 1973. In an interview at the time, Hellman described the difficulty of writing about the 1950s:

I wasn't as shocked by McCarthy as by all the people who took no stand at all....I don't remember one large figure coming to anybody's aid. It's funny. Bitter funny. Black funny. And so often something else–in the case of Clifford Odets, for example, heart-breaking funny. I suppose I've come out frightened, thoroughly frightened of liberals. Most radicals of the time were comic but the liberals were frightening.

Hellman published her third volume of memoirs, Scoundrel Time, in 1976.

In 1976, Hellman posed in a fur coat for the Blackglama national advertising campaign "What Becomes a Legend Most?". In August of that year she was awarded the prestigious Edward MacDowell Medal for her contribution to literature. In October, she received the Paul Robeson Award from Actors' Equity.

In 1976, Hellman's publisher, Little Brown, canceled its contract to publish a book of Diana Trilling's essays because Trilling refused to delete four passages critical of Hellman. When Trilling's collection appeared in 1977, a sympathetic critic in the New York Times preferred the "simple confession of error" Hellman made in Scoundrel Time for her "acquiescence in Stalinism" to Trilling's excuses for her own behavior during the McCarthy period.

Hellman presented the Academy Award for Best Documentary Film at a ceremony on March 28, 1977. Greeted by a standing ovation, she said:

I was once upon a time a respectable member of this community. Respectable didn't necessarily mean more than I took a daily bath when I was sober, didn't spit except when I meant to, and mispronounced a few words of fancy French. Then suddenly, even before Senator Joe McCarthy reached for that rusty, poisoned ax, I and many others were no longer acceptable to the owners of this industry....[T]hey confronted the wild charges of Joe McCarthy with a force and courage of a bowl of mashed potatoes. I have no regrets for that period. Maybe you never do when you survive, but I have a mischievous pleasure in being restored to respectability, understanding full well that the younger generation who asked me here tonight meant more by that invitation than my name or my history.

The 1977 Oscar-winning film Julia was based on the "Julia" chapter of Pentimento. On June 30, 1976, as the film was going into production, Hellman wrote about the screenplay to its producer:

This is not a work of fiction and certain laws have to be followed for that reason...Your major difficulty to me is the treatment of Lillian as the leading character. The reason is simple: no matter what she does in this story–and I do not deny the danger I was in when I took the money into Germany–my role was passive. And nobody and nothing can change that unless you write a fictional and different story...Isn't it necessary to know that I am a Jew? That, of course, is what mainly made the danger.

In a 1979 television interview, author Mary McCarthy, long Hellman's political adversary and the object of her negative literary judgment, said of Hellman that "every word she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the'." Hellman responded by filing a US$2,500,000 defamation suit against McCarthy, interviewer Dick Cavett, and PBS. McCarthy in turn produced evidence she said proved that Hellman had lied in some accounts of her life. Cavett said he sympathized more with McCarthy than Hellman in the lawsuit, but "everybody lost" as a result of it. Norman Mailer attempted unsuccessfully to mediate the dispute through an open letter he published in the New York Times. At the time of her death, Hellman was still in litigation with Mary McCarthy, and Hellman's executors dropped the suit.

Last years

In 1980, Hellman published a short novel, Maybe: A Story. Though presented as fiction, Hellman, Hammett, and other nonfictional people appeared as characters. It received a mixed reception and was sometimes read as another installment of Hellman's memoirs. Hellman's editor wrote to the New York Times to question a reviewer's attempt to check the facts in the novel. He described it as a work of fiction whose characters misremember and dissemble.

In 1983, New York psychiatrist Muriel Gardiner claimed that she was the basis for the title character in Julia and that she had never known Hellman. Hellman denied that the character was based on Gardiner. Because the events Hellman described matched Gardiner's account of her life and Gardiner's family was closely tied to Hellman's attorney, some believe that Hellman appropriated Gardiner's story without attribution.

Hellman died on June 30, 1984, at age 79 from a heart attack at her home on Martha's Vineyard.

Institutions that awarded Hellman honorary degrees include Brandeis University (1955), Wheaton College (1960), Mt. Holyoke College (1966), Smith College (1974), Yale University (1974), and Columbia University (1976).

Hellman's papers are held at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Human Rights Watch administers the Hellman/Hammett grant program named for the two writers.

Best films

(1977)

(1977)(Book)

(1935)

(1935)(Scriptwriter)

(1943)

(1943)(Theatre Play)

(1940)

(1940)(Scriptwriter)

(1938)

(1938)(Additional Writing)

Usually with

Filmography of Lillian Hellman (16 films)

Actress

Julia (1977)

, 1h58Directed by Fred Zinnemann

Origin USA

Genres Drama, War, Thriller, Biography, Romance

Themes Transport films, Rail transport films, Political films, Children's films

Actors Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, Jason Robards, Hal Holbrook, Rosemary Murphy, Maximilian Schell

Roles Woman in Boat

Rating70%

The young Lillian and her friend Julia, daughter of a wealthy family being brought up by her grandparents in the U.S., enjoy a childhood together and an extremely close relationship in late adolescence. Later, while medical student/physician Julia (Vanessa Redgrave) attends Oxford and the University of Vienna and studies with such luminaries as Sigmund Freud, Lillian (Jane Fonda), a struggling writer, suffers through revisions of her play with her mentor and sometime lover, famed author Dashiell Hammett (Jason Robards) at a beachhouse.

The Rehearsal (1974)

, 1h32Directed by Jules Dassin

Genres Drama, Documentary, Historical

Actors Jules Dassin, Olympia Dukakis, Laurence Olivier, Stathis Giallelis, Lillian Hellman, Melina Mercouri

Rating68%

Scriptwriter

Julia (1977)

, 1h58Directed by Fred Zinnemann

Origin USA

Genres Drama, War, Thriller, Biography, Romance

Themes Transport films, Rail transport films, Political films, Children's films

Actors Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, Jason Robards, Hal Holbrook, Rosemary Murphy, Maximilian Schell

Roles Book

Rating70%

The young Lillian and her friend Julia, daughter of a wealthy family being brought up by her grandparents in the U.S., enjoy a childhood together and an extremely close relationship in late adolescence. Later, while medical student/physician Julia (Vanessa Redgrave) attends Oxford and the University of Vienna and studies with such luminaries as Sigmund Freud, Lillian (Jane Fonda), a struggling writer, suffers through revisions of her play with her mentor and sometime lover, famed author Dashiell Hammett (Jason Robards) at a beachhouse.

The Chase (1966)

, 2h13Directed by Arthur Penn

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Thriller, Crime

Themes Films based on plays

Actors Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Robert Redford, E. G. Marshall, Angie Dickinson, Janice Rule

Roles Ecrivain

Rating70%

In a small Texas town where banker Val Rogers (E.G. Marshall) wields a great deal of influence, word comes that native son Bubber Reeves (Robert Redford) and another man have escaped from prison.

Toys in the Attic (1963)

, 1h30Directed by George Roy Hill

Origin USA

Genres Drama

Themes Films about families, Films about sexuality, Théâtre, Films based on plays

Actors Dean Martin, Geraldine Page, Gene Tierney, Wendy Hiller, Yvette Mimieux, Nan Martin

Roles Theatre Play

Rating66%

Julian Berniers returns from Illinois with his young bride Lily Prine to the family in New Orleans. His spinster sisters Carrie and Anna welcome the couple, who arrive with expensive gifts. Julian tells them that while his factory went out of business, he did manage to save money. While the sisters are skeptical, there is much talk of a long-hoped-for trip to Europe for the two sisters.

The Children's Hour (1961)

, 1h45Directed by William Wyler

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Romance

Themes Films about education, Films about children, Films about sexuality, Films about suicide, Théâtre, LGBT-related films, Films based on plays, LGBT-related films, LGBT-related film, Lesbian-related films

Actors Shirley MacLaine, Audrey Hepburn, James Garner, Miriam Hopkins, Fay Bainter, Veronica Cartwright

Roles Adaptation

Rating77%

Former college classmates Martha Dobie (Shirley MacLaine) and Karen Wright (Audrey Hepburn) open a private school for girls. Martha's Aunt Lily (Miriam Hopkins), an aging actress, lives and teaches elocution at the school. After an engagement of two years to Joe Cardin (James Garner), a reputable obstetrician, Karen finally agrees to set a wedding date. Joe is related to the influential Amelia Tilford (Fay Bainter), whose granddaughter Mary (Karen Balkin) is a student at the school. Mary is a spoiled, conniving child who bullies her classmates, particularly Rosalie Wells (Veronica Cartwright), whom she blackmails when she discovers her in possession of a student's missing bracelet.

Another Part of the Forest (1948)

, 1h47Directed by Michael Gordon

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Romance

Themes Films based on plays

Actors Fredric March, Florence Eldridge, Dan Duryea, Edmond O'Brien, Ann Blyth, John Dall

Roles Novel

Rating71%

Set in the fictional town of Bowden, Alabama in June 1880, the plot focuses on the wealthy, ruthless, and innately evil Hubbard family and their rise to prominence. Patriarch Marcus Hubbard was born into poverty and toiled at menial labor while teaching himself Greek philosophy and the basics of business acumen. He ultimately made his fortune by exploiting his fellow Southerners during the American Civil War. Shrewd, amoral elder son Benjamin is plotting to usurp his father's power and steal his money by revealing a dark secret from his days as a war profiteer. Younger son Oscar, a Ku Klux Klan supporter, lusts for whore Laurette Sincee rather than penniless neighbor Birdie Bagtry, who desperately is looking for a loan on her family's valuable land, a situation Benjamin hopes to exploit. Regina is the sexually active daughter who wants to live in Chicago with Birdie's brother, former Confederate officer John Bagtry, a move discouraged by her father, who has a disturbingly unnatural closeness to the girl. When all his offspring turn on Marcus in one way or another, their mother Lavinia - the only one in the household with any sense of morality - tells her vicious children she hopes never to see them again.

The Searching Wind (1946)

, 1h48Directed by William Dieterle

Origin USA

Genres Drama, War

Themes Political films, Films based on plays

Actors Robert Young, Sylvia Sidney, Ann Richards, Douglas Dick, Dudley Digges, Albert Bassermann

Roles Pièce de théatre

Rating60%

The North Star (1943)

, 1h48Directed by Lewis Milestone

Origin USA

Genres Drama, War, Action, Adventure

Themes Politique, Documentary films about war, Documentary films about historical events, Political films, Documentary films about World War II

Actors Anne Baxter, Dana Andrews, Walter Huston, Walter Brennan, Erich von Stroheim, Ann Harding

Roles Story

Rating59%

In June 1941 Ukrainian villagers are living in peace. As the school year ends, a group of friends decide to travel to Kiev for a holiday. To their horror, they find themselves attacked by German aircraft, part of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. Eventually their village itself is occupied by the Nazis. Meanwhile, men and women take to the hills to form partisan militias.

Watch on the Rhine (1943)

, 1h54Directed by Hal Mohr, Herman Shumlin

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Thriller, Spy

Themes Spy films, Political films, Films based on plays

Actors Bette Davis, Paul Lukas, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Lucile Watson, Beulah Bondi, George Coulouris

Roles Theatre Play

Rating70%

In 1940, German-born engineer Kurt Muller (Paul Lukas), his American wife Sara (Bette Davis), and their children Joshua (Donald Buka), Babette (Janis Wilson), and Bodo (Eric Roberts) cross the Mexican border into the United States to visit Sara's brother David Farrelly (Donald Woods) and their mother Fanny (Lucile Watson) in Washington, D.C. For the past seventeen years, the Muller family has lived in Europe, where Kurt responded to the rise of Nazism by engaging in anti-Fascist activities. Sara tells her family they are seeking peaceful sanctuary on American soil, but their quest is threatened by the presence of houseguest Teck de Brancovis (George Coulouris), an opportunistic Romanian count who has been conspiring with the Germans in the nation's capital.

The Little Foxes (1941)

, 1h55Directed by William Wyler

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Historical, Romance

Themes Théâtre, Films based on plays

Actors Bette Davis, Herbert Marshall, Teresa Wright, Charles Dingle, Richard Carlson, Carl Benton Reid

Roles Theatre Play

Rating78%

The focus is on Southern aristocrat Regina Hubbard Giddens (Bette Davis), who struggles for wealth and freedom within the confines of an early 20th-century society where a father considered only sons as legal heirs. As a result, her avaricious brothers, Benjamin (Charles Dingle) and Oscar (Carl Benton Reid), are independently wealthy, while she must rely for financial support upon her sickly husband Horace (Herbert Marshall), who has been away undergoing treatment for a severe heart condition.

The Westerner (1940)

, 1h40Directed by William Wyler

Origin USA

Genres Action, Romance, Western

Themes Films about capital punishment

Actors Gary Cooper, Walter Brennan, Fred Stone, Doris Davenport, Forrest Tucker, Paul Hurst

Rating72%

In 1882 the town of Vinegaroon, Texas is run by Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan) who calls himself "the only law west of the Pecos." Conducting his "trials" from his saloon, Bean makes a nice corrupt living collecting fines and seizing property unlawfully. Those who stand up to him are usually hanged—given what Bean calls "suspended sentences".

Dead End (1937)

, 1h33Directed by William Wyler

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Thriller, Action, Crime

Themes Films based on plays

Actors Sylvia Sidney, Joel McCrea, Humphrey Bogart, Wendy Barrie, Claire Trevor, Allen Jenkins

Rating71%

In the filthy slums of New York, wealthy people have built luxury apartments there because of the view of the picturesque East River. While they live in opulence, the destitute and dirt poor live nearby in crowded, filthy tenements.

The Spanish Earth (1937)

, 51minutesDirected by Joris Ivens

Origin USA

Genres War, Documentary

Themes Documentary films about war, Documentary films about historical events, Political films

Actors Orson Welles, Jean Renoir

Roles Writer

Rating64%

Joris Ivens tourne ce documentaire entre mars et mai 1937 pour soutenir les républicains espagnols contre l'agression franquiste. Ce film de propagande est financé par une association de soutien à la République espagnole.

These Three (1936)

, 1h33Directed by William Wyler

Origin USA

Genres Drama, Romance

Themes Films about education, Films based on plays

Actors Miriam Hopkins, Merle Oberon, Joel McCrea, Bonita Granville, Catherine Doucet, Alma Kruger

Roles Original Story

Rating73%

Following graduation, college friends Karen Wright and Martha Dobie transform Karen's Massachusetts farm into a boarding school with the assistance of wealthy benefactor Amelia Tilford, who enrolls her malevolent granddaughter Mary. Karen and local doctor Joe Cardin begin to date, unaware Martha is in love with him.

Connection

Connection